Benjamin BUTLER (1818-1893) Fine content Autograph Manuscript, 1p. 129 x 204 mm. (5 x 8 in.), [n.p., n.d. c. January 1865], a portion of a draft speech with several corrections and emendations, concerning his failed plan to use an explosive-laden ship to breach the walls of Fort Fisher which became popularly known as “Butler’s Folly.” The disastrous mistake resulted in Grant relieving Butler of command. In protest, Butler, delivered a speech on 29 January 1865 in Lowell, Massachusetts defending his conduct. The speech was published under the title: A Speech by Maj.-Gen. Benj. F. Butler, upon the Campaign Before Richmond, 1864. Delivered at Lowell, Mass., January 29, 1865 (Boston: 1865), p. 18.

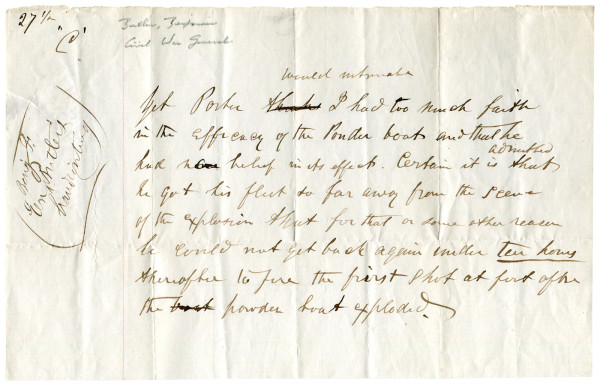

Still smarting from the disgrace of Grant’s dismissal, Butler attempts to cast the blame on Admiral David D. Porter. He writes, in full: “…Yet, Porter thinks would intimate I had too much faith in the efficacy of the Powder boat and that he had no belief in its effect. Certain it is admitted that he got his fleet so far away from the scene of the explosion that for that or some other reason he could not get back again under ten hours thereafter to fire the first shot at [the] fort after the boat powder boat exploded.” Page bears a notation in Butler’s hand, “27 1/2 ‘C’” in the upper left corner, and a collector’s ink notation in left margin “Gen. Benj. F: Butler’s handwriting”.

In October 1864, the Union Navy was assembled at Hampton Roads, Virginia, awaiting Grant to provide adequate ground support to the Navy’s impending advance on Fort Fisher, North Carolina. In November, Grant, who was preoccupied by the Union siege of Petersburg and Richmond, reluctantly agreed to detach an infantry to accompany the naval expedition to North Carolina. Grant’s inaction became General Butler’s opportunity to forward his own plan of blowing the ramparts of Fort Fisher to smithereens with an enormous floating bomb. Butler argued that Fort Fisher was particularly vulnerable because of its earthen walls, easily toppled with the right amount of explosive force. The Navy rolled out Butler’s plan to the tune of a quarter of a million dollars, outfitting the U.S.S. Louisiana with 260 tons of gunpowder, a complex detonation system, and a coat of white paint to disguise the ship as an ordinary blockade-runner.

On 23 December 1864, under the cover of darkness, with 64 vessels of the North Atlantic Squadron commanded by Admiral David Porter stationed 12 miles out to sea, the disguised U.S.S. Louisiana was towed inland by the U.S.S. Wilderness, and dropped anchor in the shallows below Fort Fisher’s Northeast bastion. Unbeknownst to everyone, the Louisiana became caught in an undertow and drifted off course. Way off course. The Union officers awaited impatiently for the explosion. At 1:40am on Christmas Eve, they were treated to a spectacular light show and all Union ships in the area received a fierce rattling, but no damage was done to Fort Fisher. “Butler’s Folly” was an incredibly expensive and embarrassing failure for the Union Army and Navy, and Grant was left with precious little alternative but to dismiss Butler from his military post.

A classic example of a disgraced officer seeking to deflect blame over his own actions by casting in on others.

Provenance: William Stackhouse Collection; Minnesota Historical Society.

Light toning, creasing, soiling and edge wear, else fine.

(EXA 5139) $700