“…things have taken an astonishing turn & we are as much in the dark as you are. A French War was expected. The declaration has been postponed, at least not taken place the 9th of April. Think of a French Alliance and Laurens President of Congress…”

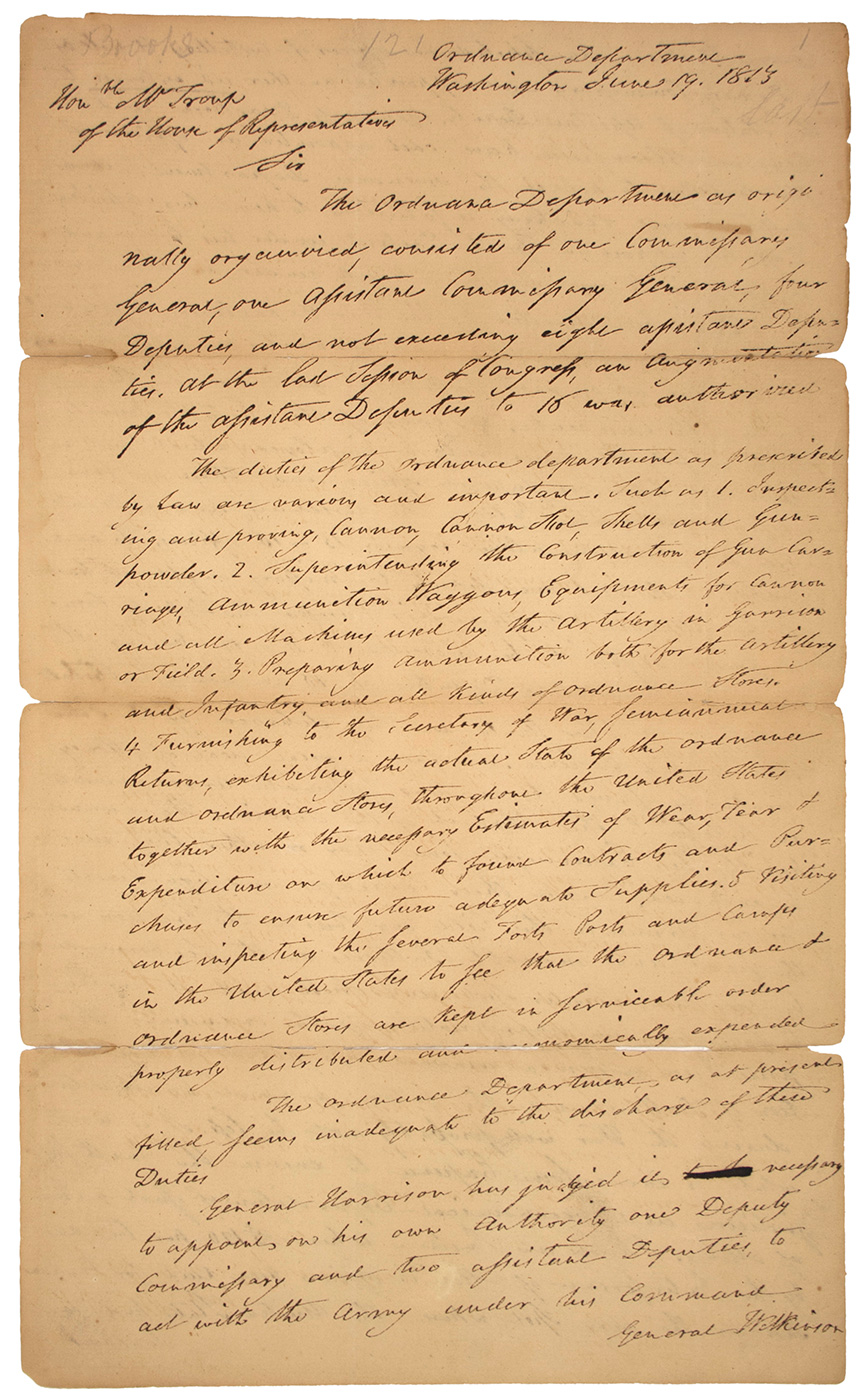

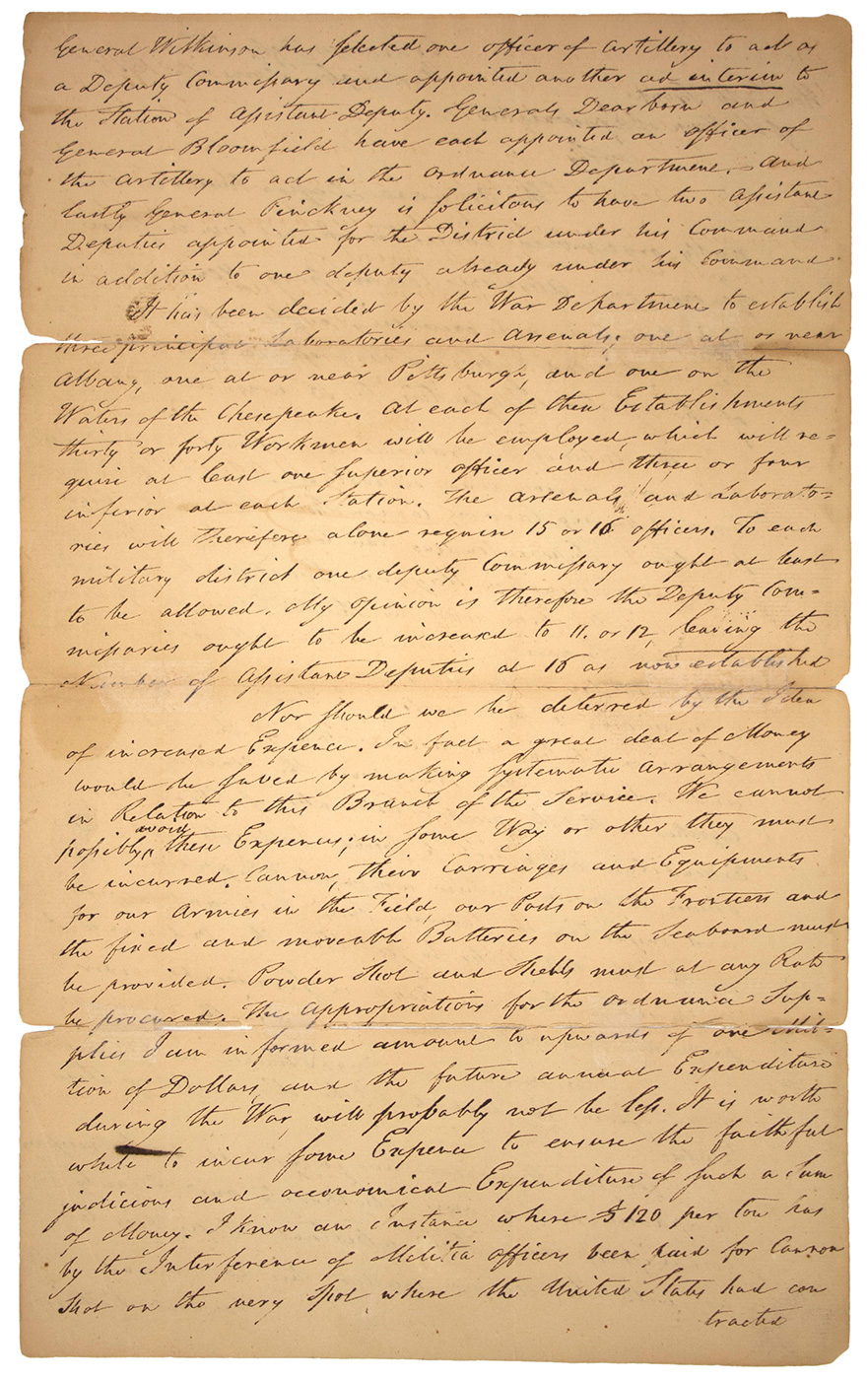

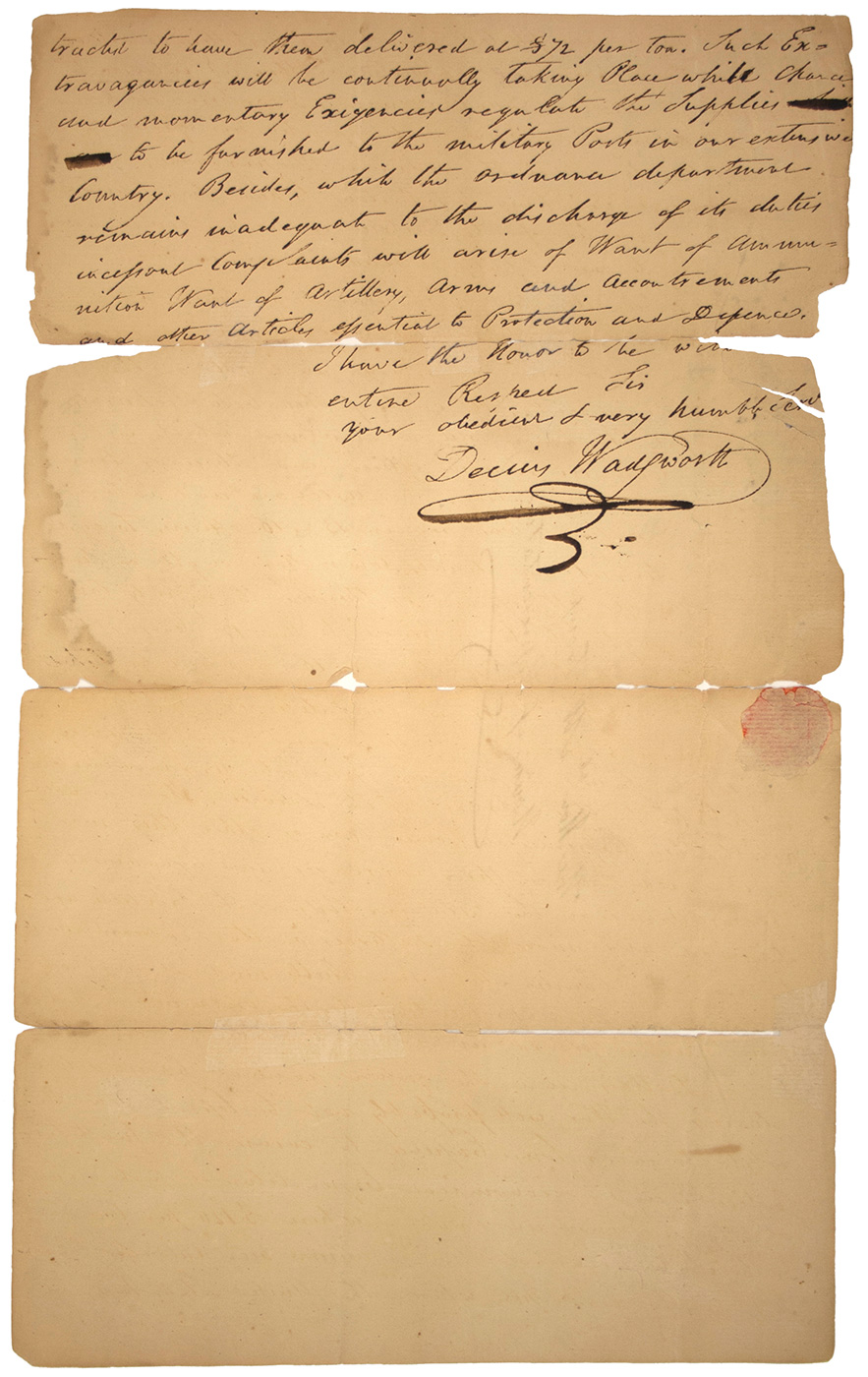

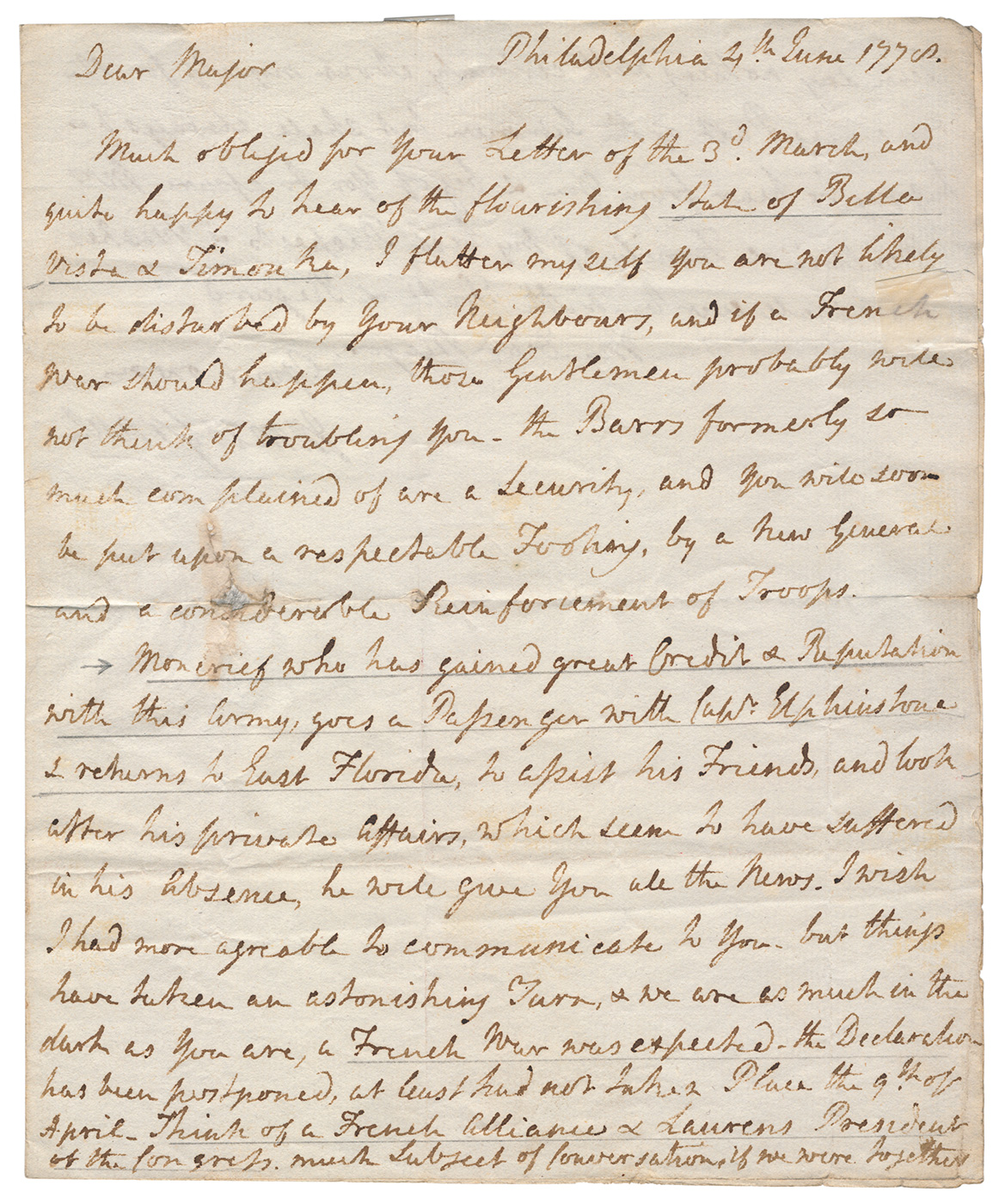

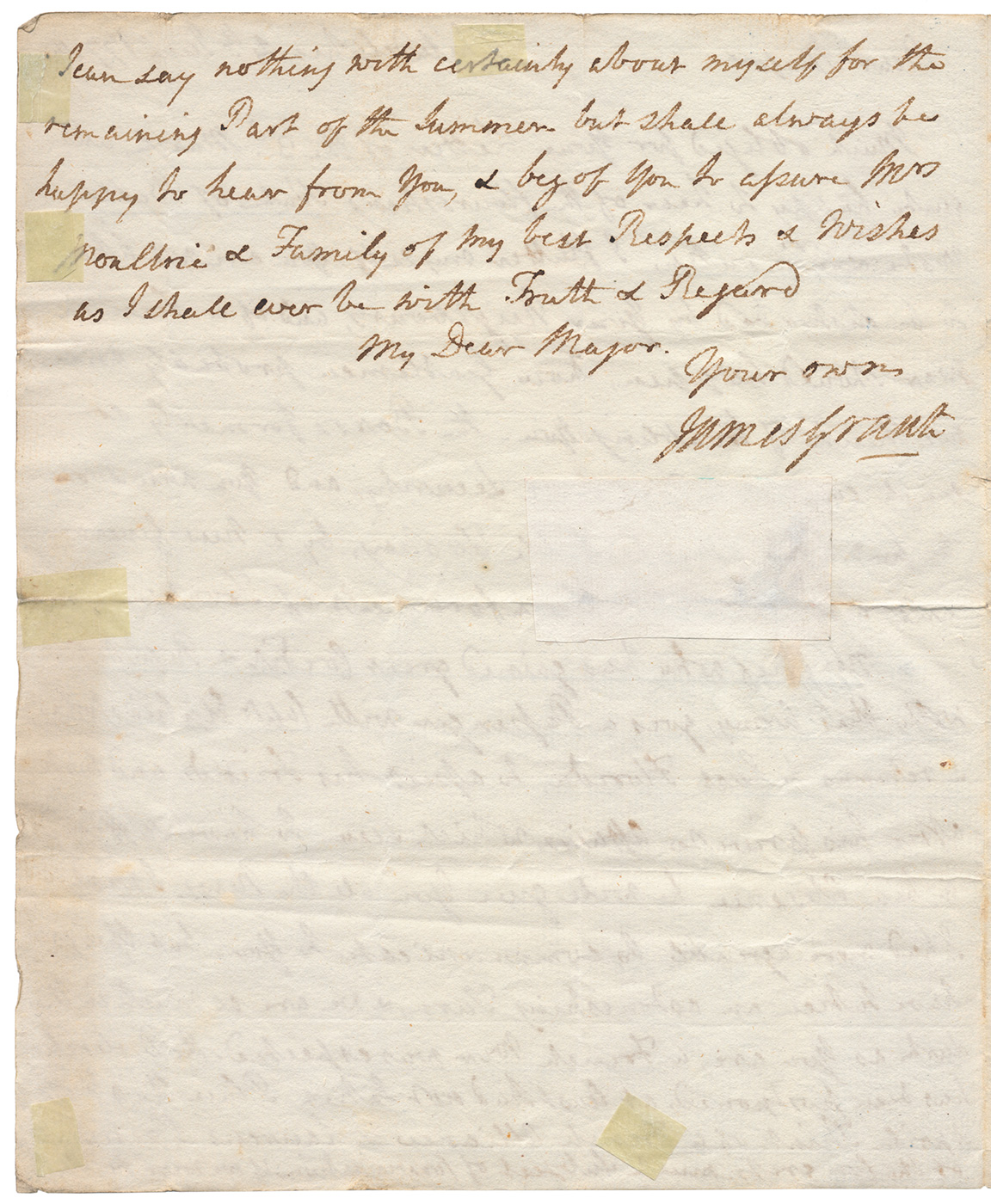

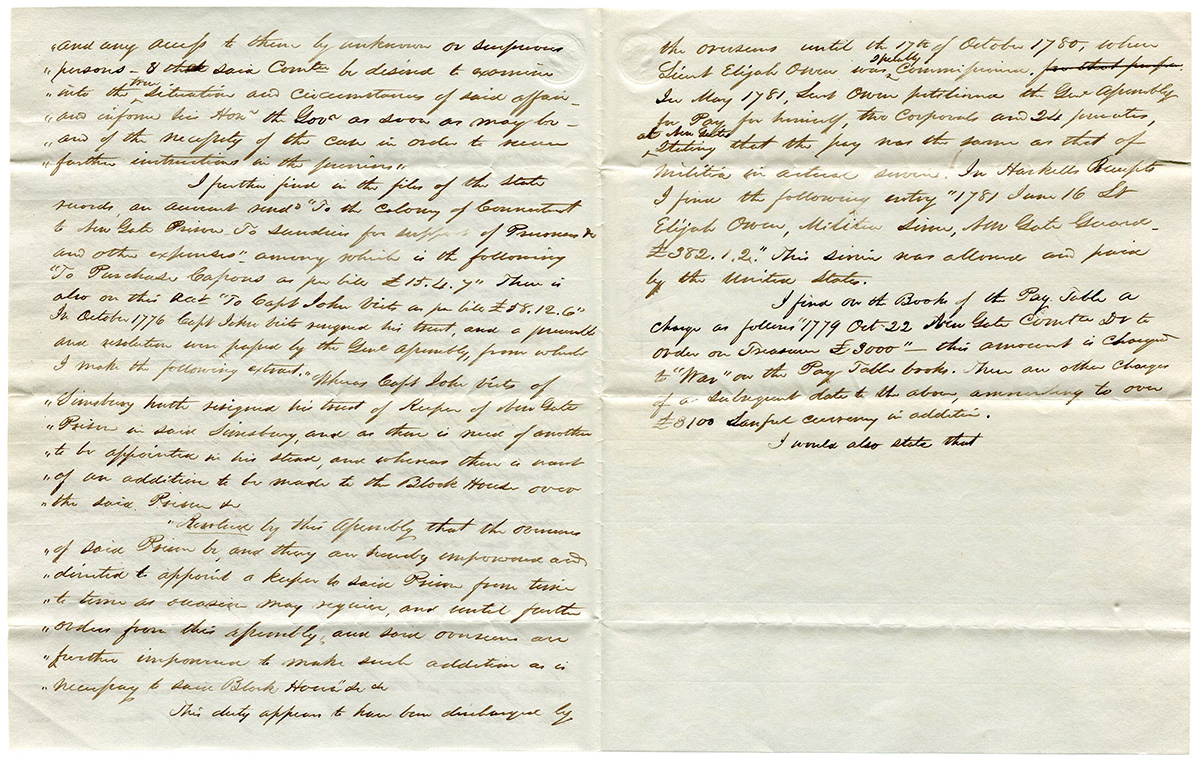

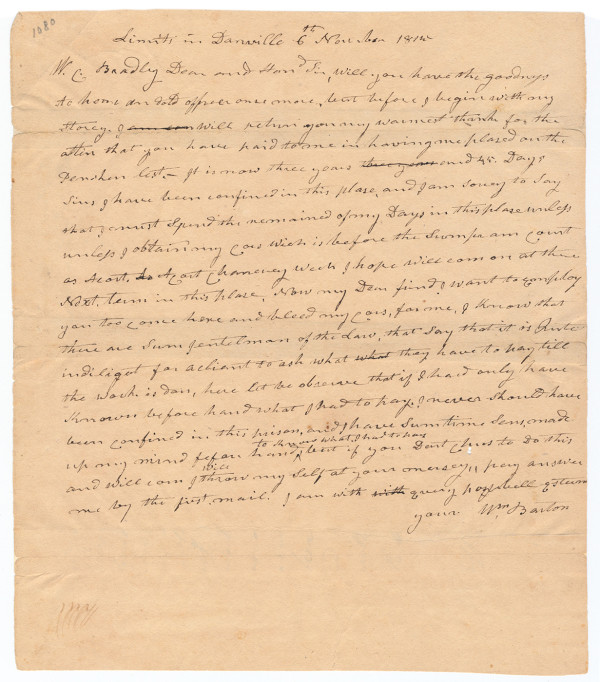

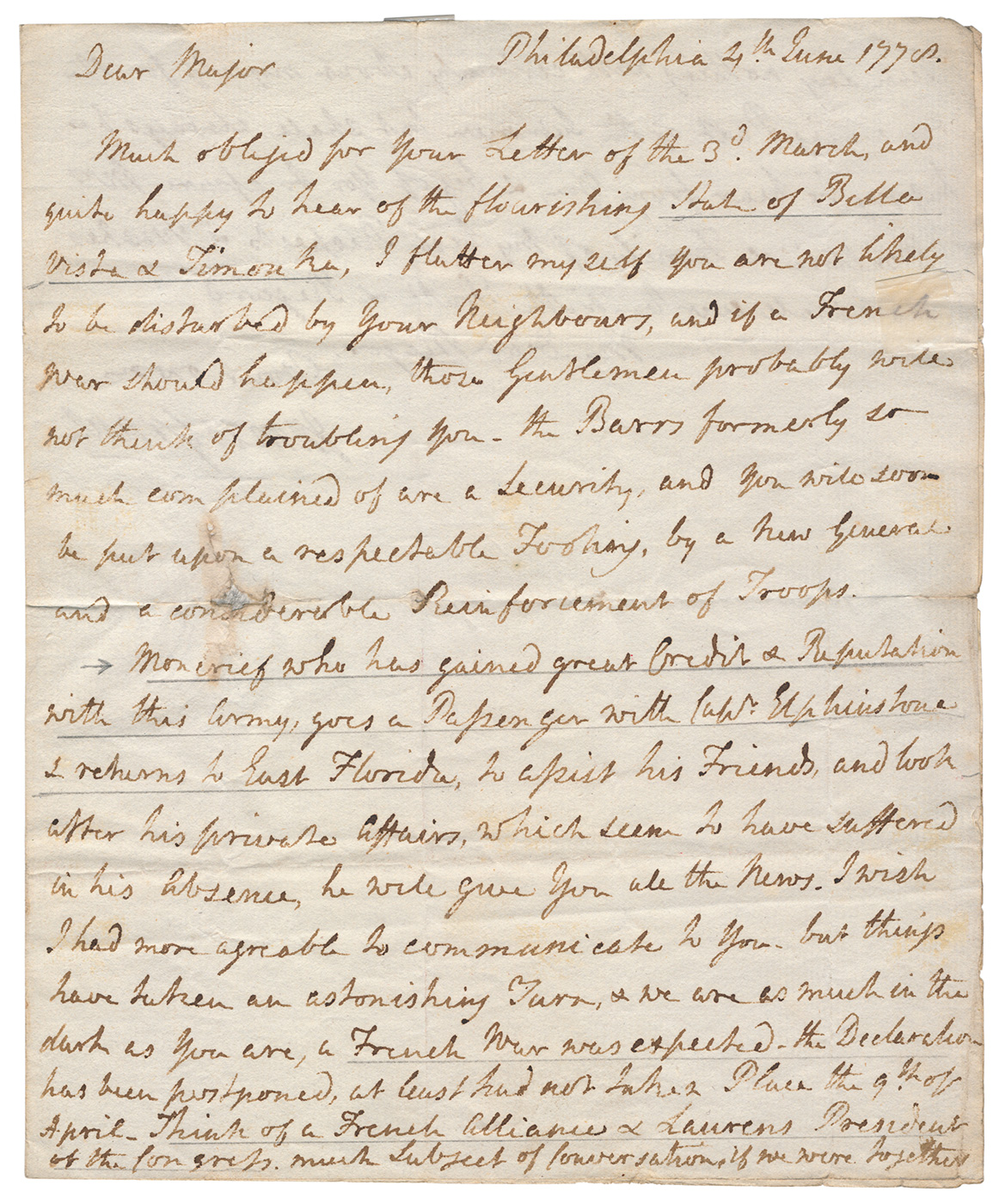

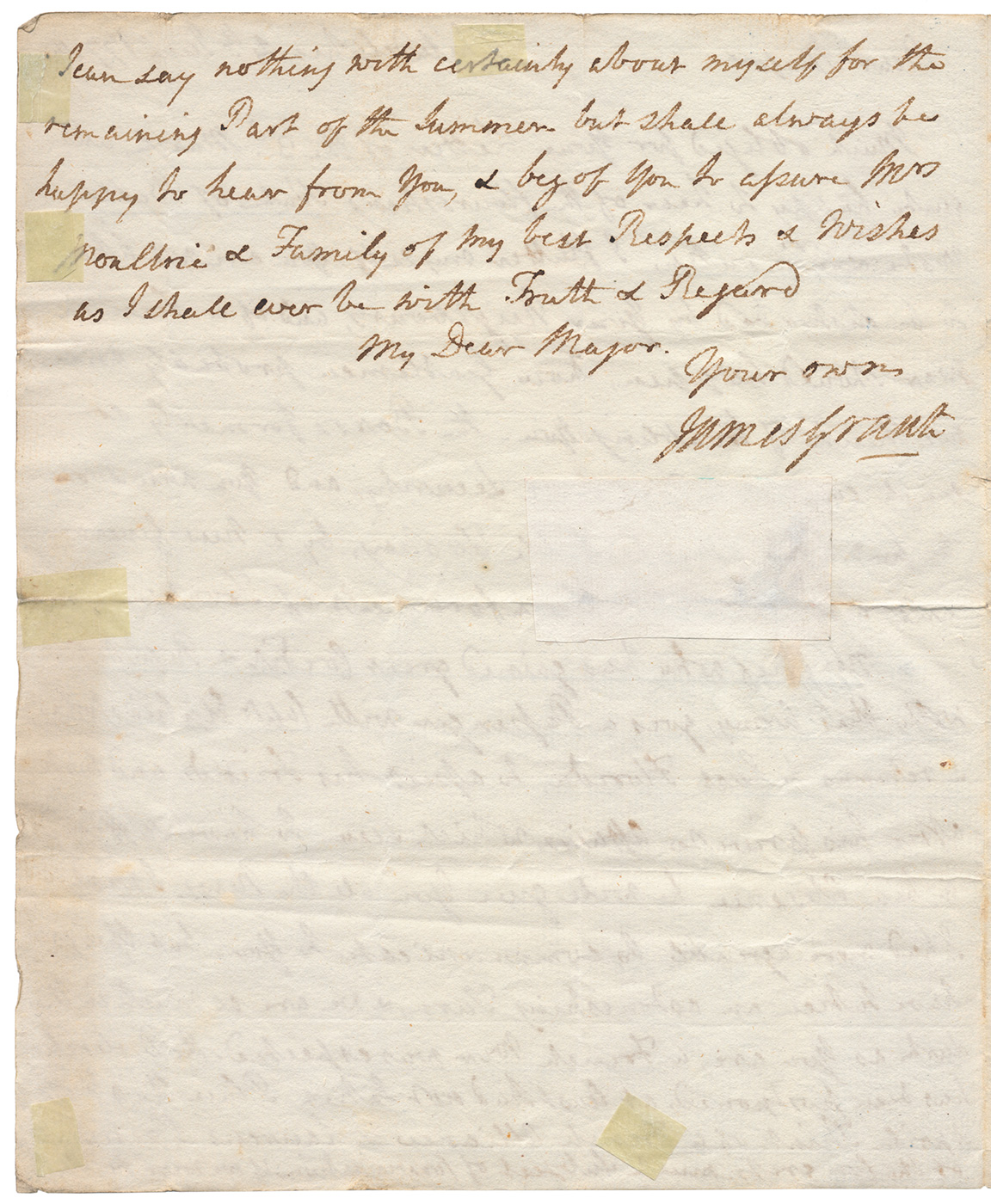

James GRANT (1720-1806) Major general in the British Army during the American Revolutionary War. Fine content war date Autograph Letter Signed “James Grant” 2pp. 224 x 184 mm. (8 7/8 x 7 1/4 in.) Philadelphia, 4 June 1778 to East Florida Lieutenant Governor John Moultrie (1729-1798), the brother of American General William Moultrie. Grant, writing from British-occupied Philadelphia, comments on the recent election of their mutual friend Henry Laurens as President of the Continental Congress. Grant also remarks on the fresh news of the Franco-American alliance that would ultimately force Great Britain to end the conflict and recognize American independence.

James GRANT (1720-1806) Major general in the British Army during the American Revolutionary War. Fine content war date Autograph Letter Signed “James Grant” 2pp. 224 x 184 mm. (8 7/8 x 7 1/4 in.) Philadelphia, 4 June 1778 to East Florida Lieutenant Governor John Moultrie (1729-1798), the brother of American General William Moultrie. Grant, writing from British-occupied Philadelphia, comments on the recent election of their mutual friend Henry Laurens as President of the Continental Congress. Grant also remarks on the fresh news of the Franco-American alliance that would ultimately force Great Britain to end the conflict and recognize American independence.

“Much obliged for your letter of the 3rd March and quite happy to hear of the flourishing state of Bella Vista & Timonka. I flatter myself you are not likely to be disturbed by your neighbors and if a French war should happen, those gentleman probably would not think of troubling you — the Barrs formerly so much complained of are a security, and you will soon be put upon a respectable footing by a new general and considerable reinforcement of troops. [James] Moncreif who has gained great credit & reputation with this army, goes a passenger with Capt. Elphius Lowe & returns to East Florida to assist his friends and look after his private affairs which seemed to have suffered in his absence. He will give all the news. I wish I had more agreeable to communicate to you but things have taken an astonishing turn & we are as much in the dark as you are. A French War was expected. The declaration has been postponed, at least not taken place the 9th of April. Think of a French Alliance and Laurens President of Congress. Much subject of conversation if we were together. I can say nothing for certainty about myself for the remaining part of the summer but shall always be happy to hear from you & beg of you to assure Mrs. Moultrie & family of my best respects & wishes as I shall ever be with truth and regard…”

Unbeknownst to the general, Great Britain had already declared war on France on 17 March 1778 following Louis XVI’s decision to recognize American independence on 6 February. Word of the treaty with France had only arrived in the Americas at the beginning of May. Coincidentally, on the same day that Grant wrote the present letter, the Lancaster-based Pennsylvania Packet reported that “a gentlemen arrived at Elizabeth town on Saturday last, from New York, who brought an account that war had been declared there that day in form, against France…” Official reports of the British declaration began trickling in several days later.1 Two weeks after he wrote to Moultire, Grant joined the British Army in evacuating Philadelphia and commanded two brigades at the Battle of Monmouth (28 June). The following year, Lord Germain ordered Grant to the West Indies to supervise the construction of British garrisons in the islands.

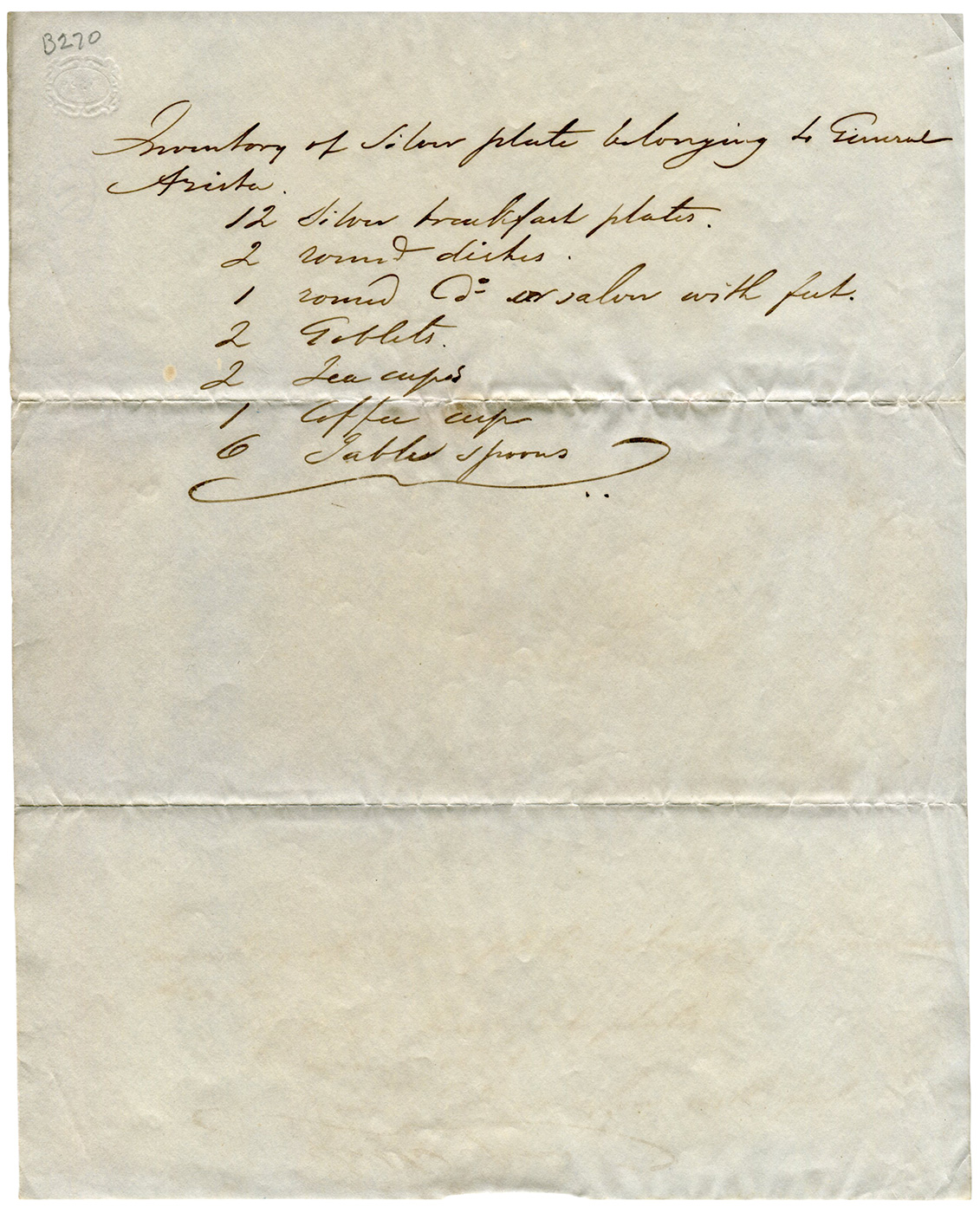

Prior to the outbreak of the Revolutionary War, Grant, John Moutlrie, and Henry Laurens were close friends business and associates. They became acquainted during the French and Indian War when Grant led a force of 2,600 in South Carolina against the Cherokee in 1761. Following the war, Grant served as the first British governor of East Florida (1764-1771), and John Moultrie became his Lieutenant Governor. Both Grant and Moultrie purchased plantations in Florida. Moultrie’s properties were named “Bella Vista & Timonka” while Grant operated an indigo plantation he named “Villa” as well as another, “Mount Pleasant,” which produced rice. To staff his properties, Grant purchased approximately 70 slaves — most of whom came from Henry Laurens, who also happened to be a prominent Charleston slave trader.2

Prior to the outbreak of the Revolutionary War, Grant, John Moutlrie, and Henry Laurens were close friends business and associates. They became acquainted during the French and Indian War when Grant led a force of 2,600 in South Carolina against the Cherokee in 1761. Following the war, Grant served as the first British governor of East Florida (1764-1771), and John Moultrie became his Lieutenant Governor. Both Grant and Moultrie purchased plantations in Florida. Moultrie’s properties were named “Bella Vista & Timonka” while Grant operated an indigo plantation he named “Villa” as well as another, “Mount Pleasant,” which produced rice. To staff his properties, Grant purchased approximately 70 slaves — most of whom came from Henry Laurens, who also happened to be a prominent Charleston slave trader.2

Grant also discusses the departure of James Montcrief (1741-1793). Montcrief was a military engineer who took part in numerous campaigns during the Revolutionary War. He came to America in 1763 in the employ of Governor Grant of East Florida and drafted a current map of St. Augustine. In 1779 he was appointed Chief Engineer, responsible for the defenses of Savannah and during the following year he would take part in the Siege of Charleston. In 1780, Montcrief took command of the Black Pioneers, a Loyalist force composed of freed slaves.

An excellent historical and association piece that highlights the network of personal and familial relationships in Colonial America wrenched apart by the Revolutionary War.

Expected folds with minor separations repaired in serval places with glassine and period paper, small loss to first page only marginal wear, else very good.

(EXA 5382) SOLD

_________

1 Pennsylvania Packet, (Lancaster) 6 June 1778, 3; Connecticut Courant (Hartford) 9 June 1778, 3: “…March 17. A Privy Council is summoned to meet this day at St. James after the levee is over said to be on the issuing a proclamation for the declaration of war against France…”

2 James Grant Papers, National Archive of Scotland. The archive includes several bills from Laurens invoicing Grant for slaves.