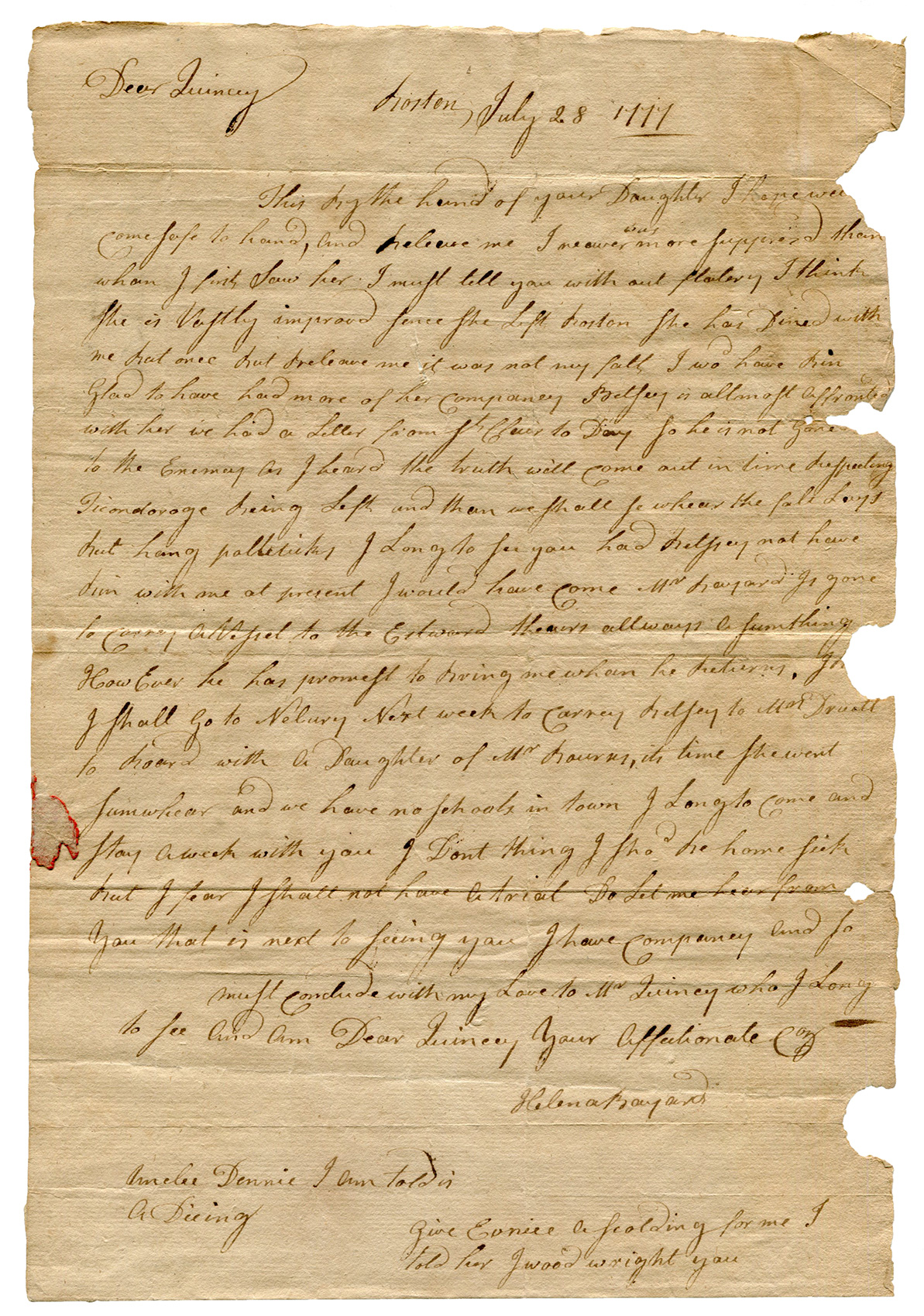

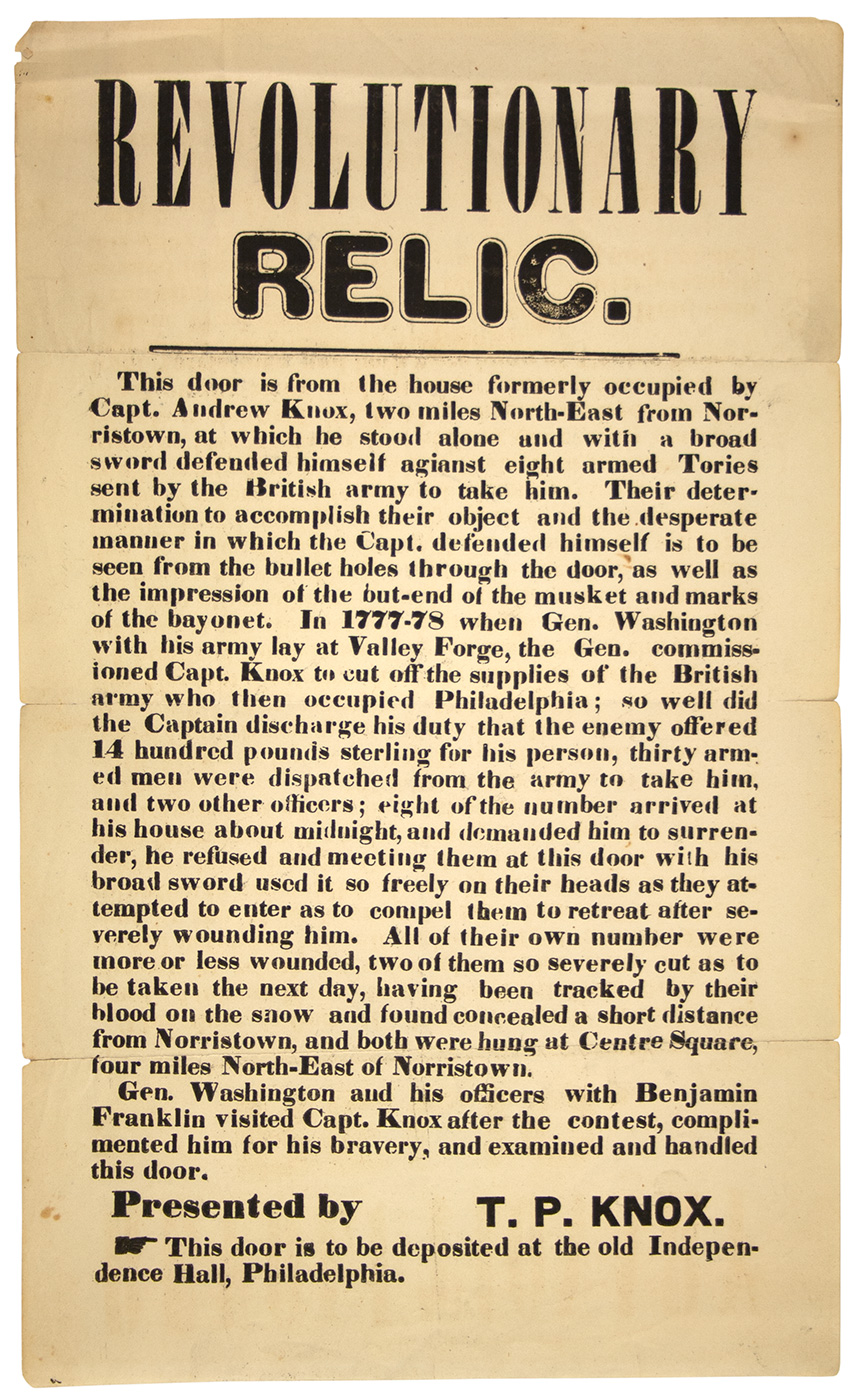

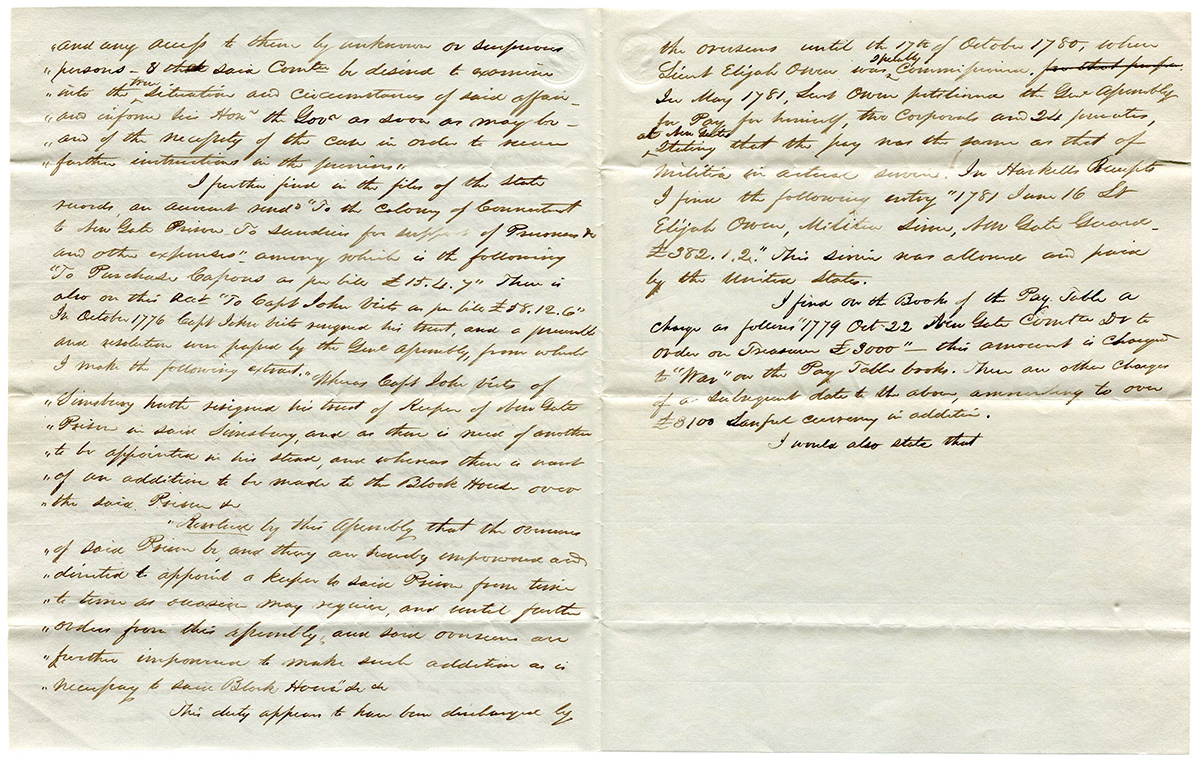

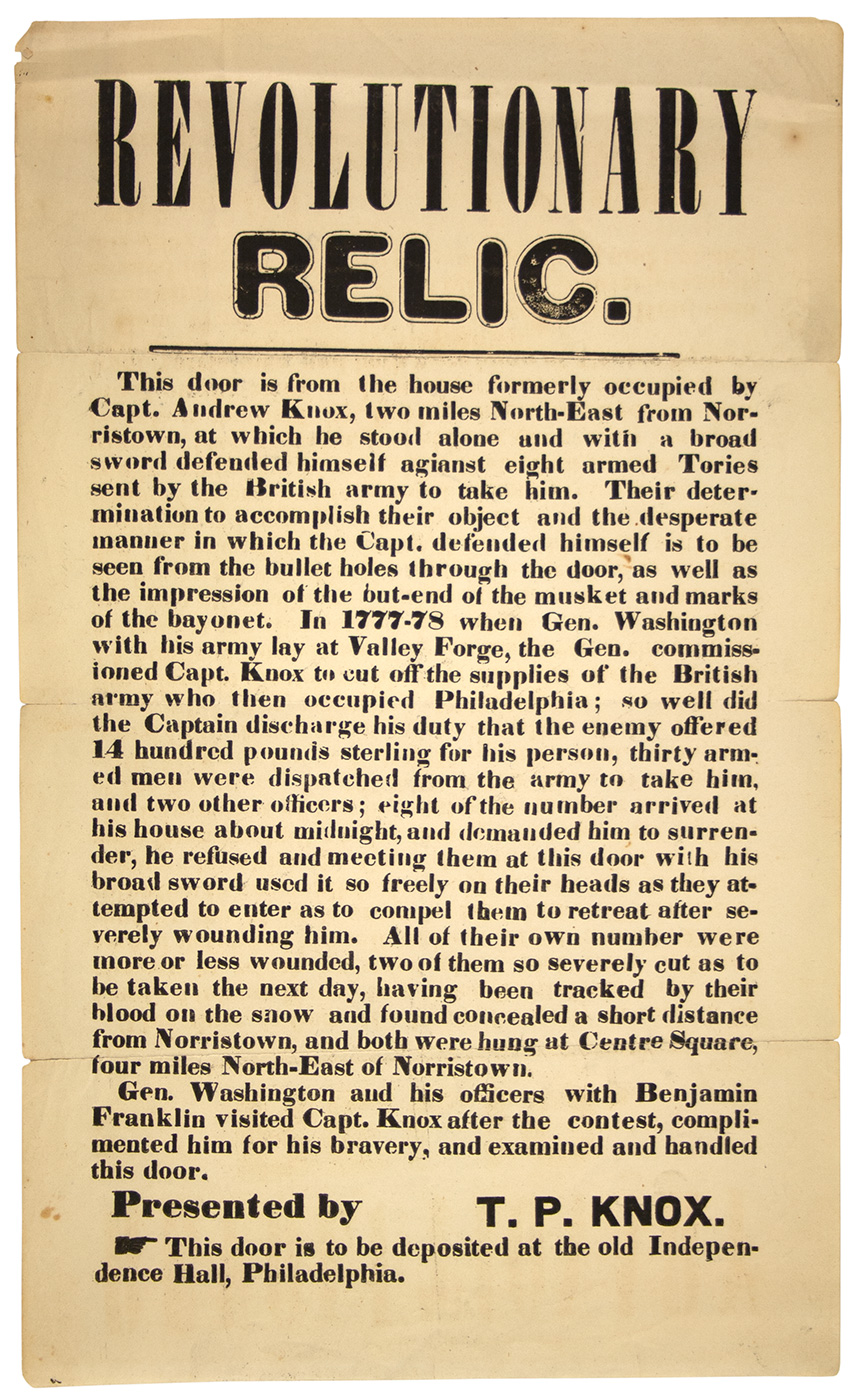

(American Revolution) Broadside, “REVOLUTIONARY RELIC.” (Pennsylvania, c. 1860) 351 x 212 mm. (13 7/8 x 8 3/8 in.) A highly unusual broadside telling the story of the loyalist attack on the home of Captain Andrew Knox in 1778 and identifying “This door” as the same that protected Knox from his assailants (with the bullet holes to prove it).

(American Revolution) Broadside, “REVOLUTIONARY RELIC.” (Pennsylvania, c. 1860) 351 x 212 mm. (13 7/8 x 8 3/8 in.) A highly unusual broadside telling the story of the loyalist attack on the home of Captain Andrew Knox in 1778 and identifying “This door” as the same that protected Knox from his assailants (with the bullet holes to prove it).

The broadside describes the “Relic” as “This door…from the house formerly occupied by Capt. Andrew Knox, two miles North-East from Norristown, at which he stood alone and with a broad sword defended himself against eight armed Tories sent by the British Army to take him. Their determination to accomplish their object and the desperate manner in which the Capt. defended himself is to be seen from the bullet holes through the door, as well as the impression of the but-end of the musket and marks of the bayonet. In 1777-78 when Gen. Washington with his army lay at Valley Forge, the Gen. commissioned Capt. Knox to cut off the supplies of the British army who then occupied Philadelphia; so wee did the Captain discharge his duty that the enemy offered 14 hundred pounds sterling for his person, thirty armed men were dispatched from the army to take him, and two other offices; eight of the number arrived at his house about midnight, and demanded him to surrender, he refused and meeting them at this door with his broad sword used it so freely on their heads as they attempted to enter as to compel them to retreat after severely wounding him. All of their own number were more or less wounded, two of them so severely cut as to be taken the next day, having been tracked by their blood on the snow and found concealed a short distance from Norristown, and both were hung at Centre Square, four miles North-East of Norristown. Gen. Washington and his officers with Benjamin Franklin visited Capt. Knox after the contest, complimented him for his bravery, and examined and handled this door.” Signed in print by “T[homas].P. Knox” who promises “This door is to be deposited at the old Independence Hall, Philadelphia.”

Thomas P. KNOX (c. 1809-1879) was the son of Andrew Knox, Jr. (1773-1844), the youngest son of Andrew Knox, Sr. Thomas was educated at Rutgers and became a prominent resident who dedicated his life to the improvement of farming methods, and for some time served as a justice of the peace, and an aide to the Governor of Pennsylvania. Inspired by his family’s revolutionary past, Knox took an interest in historical preservation, and in the 1870s led efforts to purchase George Washington’s Valley Forge headquarters.1

Whether the bullet-ridden door ever arrived at Independence Hall has not been determined.2 In 1895, a local antiquarian recalled interviewing the widow of Andrew Knox’s eldest son, Robert (1756-1814), who showed him the famous door and regaled him with stories of the incident in the late 1840s and early 50s.3 The earliest known printed reference to the door comes in 1859 in a local history describing the Knox homestead in Whitpan Township, “where the bullet holes, seven in number, are shown in the door. His grandson, Colonel Thomas P. Knox, late Senator from the county, resides within the present limits of Norristown.”4 The next reference to the “Knox Door” comes in 1863 at an exhibition of the Pennsylvania Agricultural Society in Norristown. At that exhibition, Colonel Knox again asserted the door would “be placed in Independence Hall shortly.”5 It appears that did not occur before the colonel’s death in 1879. If it did, it may have been displayed temporarily during the 1876 Centennial celebrations in Philadelphia (and two years later it was exhibited for the centennial of Valley Forge in 1778).6 In 1884, the Colonel’s daughter, Ellen, exhibited the door at a fair held in honor of the Centennial of Montgomery County at the courthouse in Norristown. This time there was no mention of a donation to Independence Hall.7 We have yet to discover any reference to the door in published sources beyond this time.

Like many 19th century accounts of the Revolutionary War, especially when told by family members, this tale is filled with hyperbole and some historical impossibilities. While we may rightly scoff at the notion of Benjamin Franklin taking time off from his diplomatic mission in France to personally congratulate Knox, the core of the story is true and documented.8 Andrew Knox (1727-1807) was a prominent resident of Norristown, Pennsylvania — a militia leader who in 1778 was part of an effort to prevent supplies from the countryside from getting to British-occupied Philadelphia, while George Washington’s army starved at Valley Forge only a few miles away. In repayment for his efforts, a party of Loyalists attacked Knox in his home in February 1778, only to be repelled, but not after riddling his door with musket balls. Contemporary sources record a November 1778 trial of Abijah Wright, a Philadelphia laborer, accused of attacking “with force of arms… the dwelling House of Andrew Knox, Esq… feloniously and burglariously … an intent…to kill and murder, &ca., &ca…” Wright, a member of a notorious family of Tories, was found guilty of these crimes and of “treason” and ordered executed.9 The trial of Abijah was part of a purge of Loyalists in Pennsylvania following the British evacuation of Philadelphia in the summer of 1778. Pennsylvania Attorney General Jonathan Dickinson Sergeant and his special assistant Joseph Reed prosecuted over forty defendants — thirty-three for treason with eight executed. Interestingly, Abijah Wright’s trial was carried over a month due to questions as to the defendant’s sanity.10 Before he pronounced the death sentence, the chief justice admonished him for his actions: “You have in the dead of night, with a number of desperate ruffians, broke and entered the mansion house of Colonel11 Andrew Knox… then peaceably in his bed… You broke and entered this house in a hostile manner, with arms in your hands and with an intent to murder the owner, having discharged many loaded muskets at him. It has been alleged, that you might have intended not to murder him, but to carry him away a prisoner to the enemy, then in possession of this city…” The judge also noted that Knox nearly singlehandedly fought off his attackers, with the assistance of his son Robert.12

As time went on, and memories faded, the story of Andrew Knox changed. The account that appears in Andrew Knox’s 1808 obituary is strikingly different that what Col. Thomas P. Knox related in his broadside, but is quite detailed and merits quoting at length:

“Andrew Knox.—Died at his house in Whitpain township, the 17th. ult… in the 80th. year of his age…The friends of the American Revolution will be gratified by the recital of an incident in his life, which connects his name with that revolution. His office, a magistrate, procured him the honor of a visit from certain Royalists, when the British army held the city of Philadelphia. About 4 o’clock in the morning of the 14th of February 1778, seven armed refugees approached his house, two stood sentry at the back window, while the other five attempted the door. Finding it bolted, they endeavored to gain admittance by artifice. Squire Knox, partly dressed, came to the door at their call, when a dialogue took place nearly as follows: K. ‘What do you want?’ R. ‘I came to tell you that the enemy are coming, and to warn you to escape for your life.’ K. ‘What enemy 1’ R. ‘The British.’ K. ‘And who are you that speak?’ (A friendly name was given, and on looking out the window the Squire saw their arms in the moonlight.) K. ‘I believe you are the enemy.’ Upon this they burst the door and attempted to force their way in. Mr. Knox seizing the open door with his left hand, with his cutlass in the other, saluted the aggressors in a manner they did not expect, and repeated his strokes. The assailants meanwhile, made repeated thrusts with their bayonets, from which Mr. Knox received two or three slight flesh wounds, and had his jacket pierced in several places, but the door standing ajar, covered his vitals and saved his life. By this time Mr. Knox’s eldest son, then a young stripling, having laid hold of a gun loaded with small shot, came to the scene of action and asked his father if he should shoot. The Squire having just broke his cutlass on one of the enemy’s guns, now apprehended that he must surrender, and thinking it imprudent to exasperate the foe to the utmost, told his son not to shoot, trying his weapon further and finding it capable of service, he continued to defend the pass, and his son wishing to co-operate struck one of the assailants with the barrel of his gun and brought him to his knees (and to his prayers, it is hoped). This gave the besighed [sic] an opportunity to close the door, whereupon the party presented their pieces and fired five balls through the door. Whether it arose from deliberation or from the scattered position of the men, so it was that some of these balls passed through the door directly and others obliquely, so as to hit a person standing by the side: and in fact, Squire Knox, who stood there as a place of safety, received a touch by one of them. Thus foiled in their object and perhaps that the report of their guns would alarm the neighborhood, the men commenced a retreat towards the city. Squire Knox having at the approach of day collected some friends and armed men went in pursuit. They tracked the blood several miles. One of whom had taken refuge in a house was taken, brought back and made an ample confession. This fellow being found to be a deserter from the American army was tried by court martial for the desertion only, condemned and executed near Montgomery Square. Another was apprehended after the British left the city, condemned by a civil court and executed. Of the rest little is known.”13

While we see many details repeated, there is no visit from Washington or Franklin. The account is also nuanced enough to note the specific fate of two of the men who were captured, including Abijah Wright, the second person tried and executed “by a civil court.”

Sometime in the 19th century, probably to make the story appear more significant to listeners, George Washington materialized, and then, amazingly, Benjamin Franklin, both of whom apparently examined and handled the door.14

Minor partial separations at horizontal folds, a few foxed spots with minor edge wear, else very good.

(EXA 5359) $950

1 Historical Society of Montgomery County, Historical Sketches: a Collection of Papers, Volume 1. (1895), 285.

2 The National Park Service is unaware of any donation of a door associated with the event, though collection records dating from before the 1930s are not complete. (The site did not come under the administration of the National Park Service until 1948). Diethorn, Letter to the Author, 23 Jan. 2014, who extends his thanks for their gracious and valuable assistance in sourcing additional references for this story.

3 Rev. Charles Collins “Norriton Presbyterian Church and Collateral Gleanings of the Early Settlers” Historical Society of Montgomery County, ed., Historical Sketches: a Collection of Papers, Volume 1. (1895), 285: “Pursuing my investigations between 1845-’55, I was several times entertained by Mrs. Margaret Knox, widow of Robert Knox, who was the oldest son of Capt. Andrew Knox. The latter was somewhat renowned in his day, from the circumstance that an unexpected assault was made on upon him by some Tories one night (February 14, 1778) during the Revolutionary War. While there appeared to be threatenings on the part of these evil disposed men, they were unsuccessful, and were driven off, Capt. Knox holding the fort. His son Robert, above alluded to… was a witness and present when the affray occurred, and lived for many years after, to recount the hair-breath escape of those dangerous night prowlers. During our interviews, Mrs. Knox would often expatiate with much earnestness in describing the eventful scene, exhibiting to me the front door of the farm house, that had been pierced with a number of bullet holes, and which door, subsequently, was given to Independence Hall, Philadelphia, as a relic of those troublous times.”

4 William J. Buck, History of Montgomery County, (1859), 89.

5 “Eleventh Exhibition of the Pennsylvania State Agricultural Society” Farmer and Gardner Vol. 5, 1863, 105. In describing the various exhibits the author noted “…a rare revolutionary relic in the shape of a door, behind which, Capt. Andrew Knox, the father of the president of the society, successfully defended himself, against the fierce attack of eight tories, sent by the British to capture him. The door bears numerous evidences of the fierceness of the combat. It is perforated in many places with musket balls, and is scarred all over with the sword-cuts, inflicted by the sword of the courageous captain. Gen. Washington, Lafayette, Franklin and many other distinguished men have handled this door. It is to be placed in Independence Hall shortly.”

6 Diethorn, Letter to the Author, 23 Jan. 2014. The curator was aware of numerous objects being displayed temporarily exhibited at Independence Hall; The Times (Philadelphia) 19 June 1878,1.

7 Gotwalts Hobson Freeland, William Joseph Buck, Henry Sassaman Dotterer, The Centennial Celebration of Montgomery County: At Norristown, Pa., September 9, 10, 11, 12, 1884: an Official Record of Its Proceedings (1884), 123-124.

8 Franklin departed Philadelphia for France in December 1776, he did not return to America until 1785.

9 Minutes of the Supreme Executive Council of Pennsylvania (30 Nov. 1778), 631-632; Massachusetts Spy, 31 Dec. 1778, 3; See Lieut. Col. Jacob Reed, proceedings at the Dedication of the Monument Erected to his Memory… (1905), 50-52.

10 Jack D. Marietta, Gail Stuart Rowe, Troubled Experiment: Crime and Justice in Pennsylvania, 1682-1800, (2008), 188.

11 Most contemporary mentions of Andrew Knox refer to him as “Colonel.” 19th century accounts refer to him as “Captain.”

12 Pennsylvania Gazette (Philadelphia), 19 June 1878,1. The judge continued to berate Wright: “This is so far from being an extenuation of your guilt, that it is an aggravation of it; for you, in such a case, would have been guilty of treason. Because this gentleman had preferred the good of his country and of posterity to his present personal ease and safety, and in compliance with the dictaes of a good conscience had taken up arms to defend himself, his posterity, his liberties, and the just rights of mankind, and had been distinguished by his fellow citizens in being made a Colonel of the militia; you, his countryman, his neighbor, formerly his father’s tenant, and who had partaken of his benevolence, attempted to put him into the power and under the dominion of his inveterate foes, foes to God and man, by whom you were sure he would at least have been confined in a loathsome dungeon, if not assassinated or starved to death. But he, with the assistance of his son, discomfited seven of you, whatever your wicked purposes might have been…”

13 Norristown Register, 6 Nov. 1808.

14 The Times (Philadelphia), 19 June 1878, “Washington, while his army lay at the Forge, commissioned Captain Knox to cut off the supplies of the British…. so well did the Captain discharge his duty that the enemy offered £1,400 his person, and thirty armed men were dispatched from the army to take him and two other officers. Eight of these arrived at his dwelling at midnight and commanded him to surrender. He refused, and, meeting them at the door, he used the sword so freely upon their heads as to compel them to retreat… After the contest General Washington and his officers, with Benjamin Franklin, visited Captain Knox, complimented him for his bravery and examined and handled his door.”

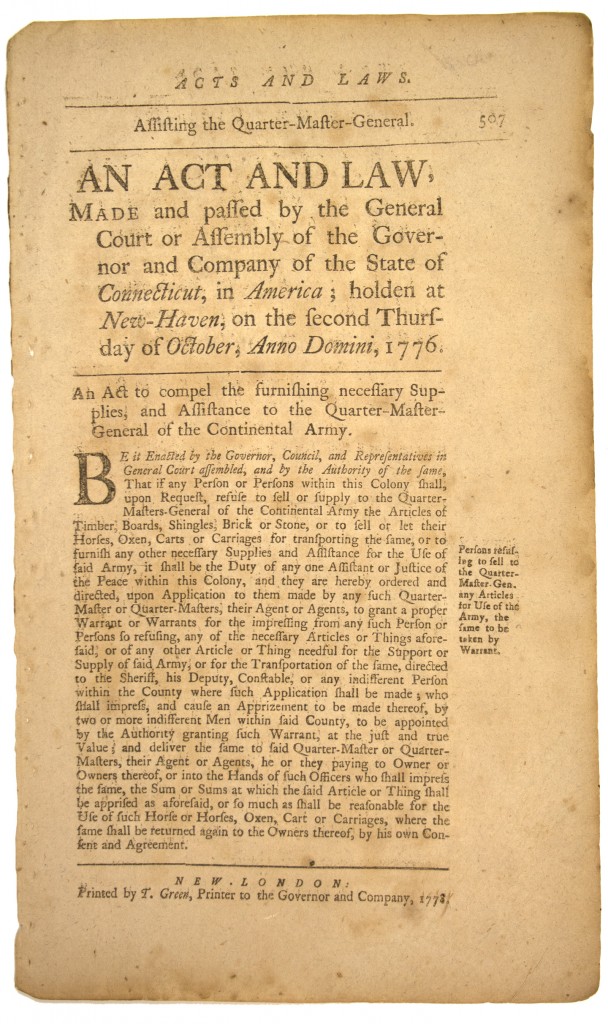

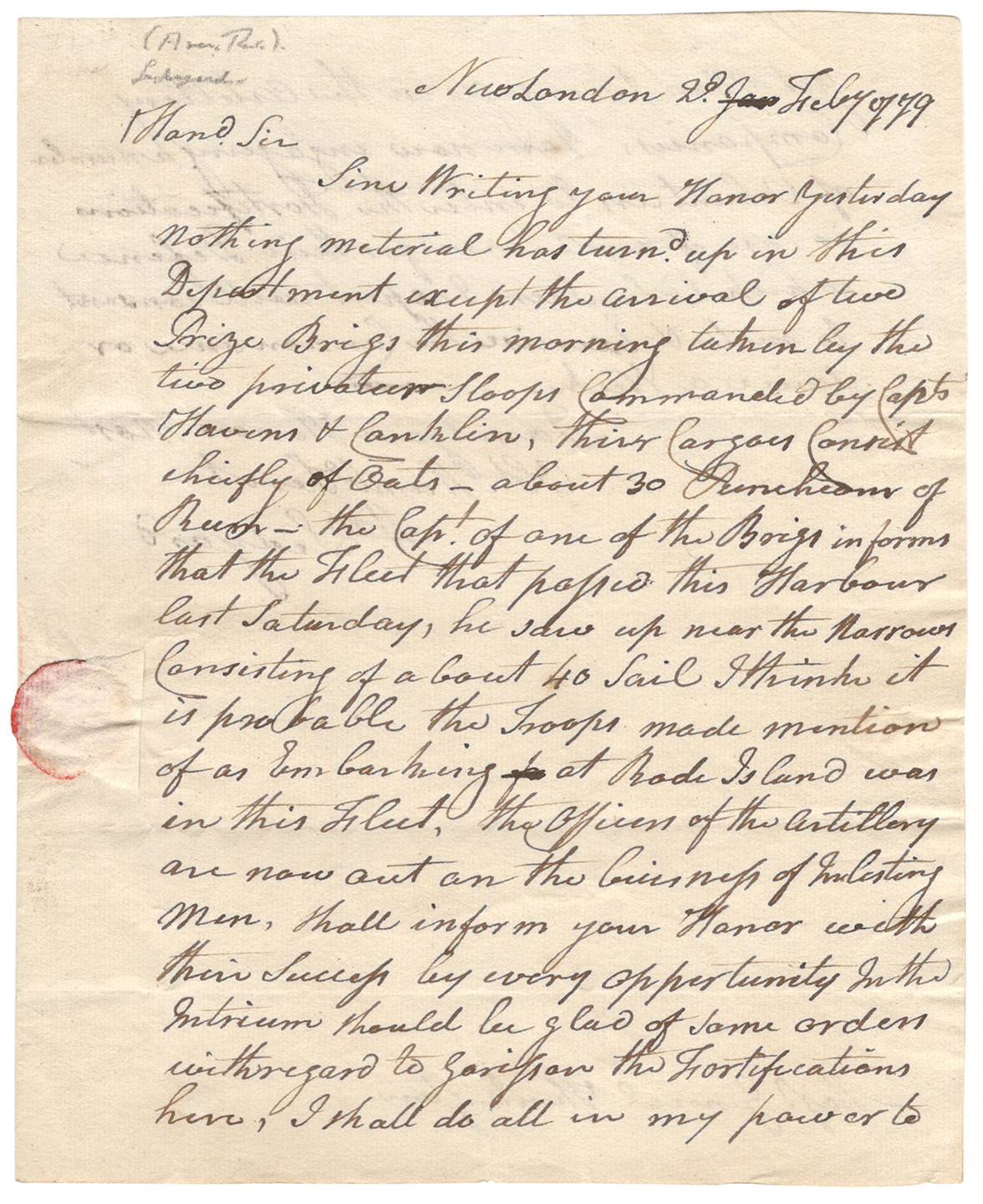

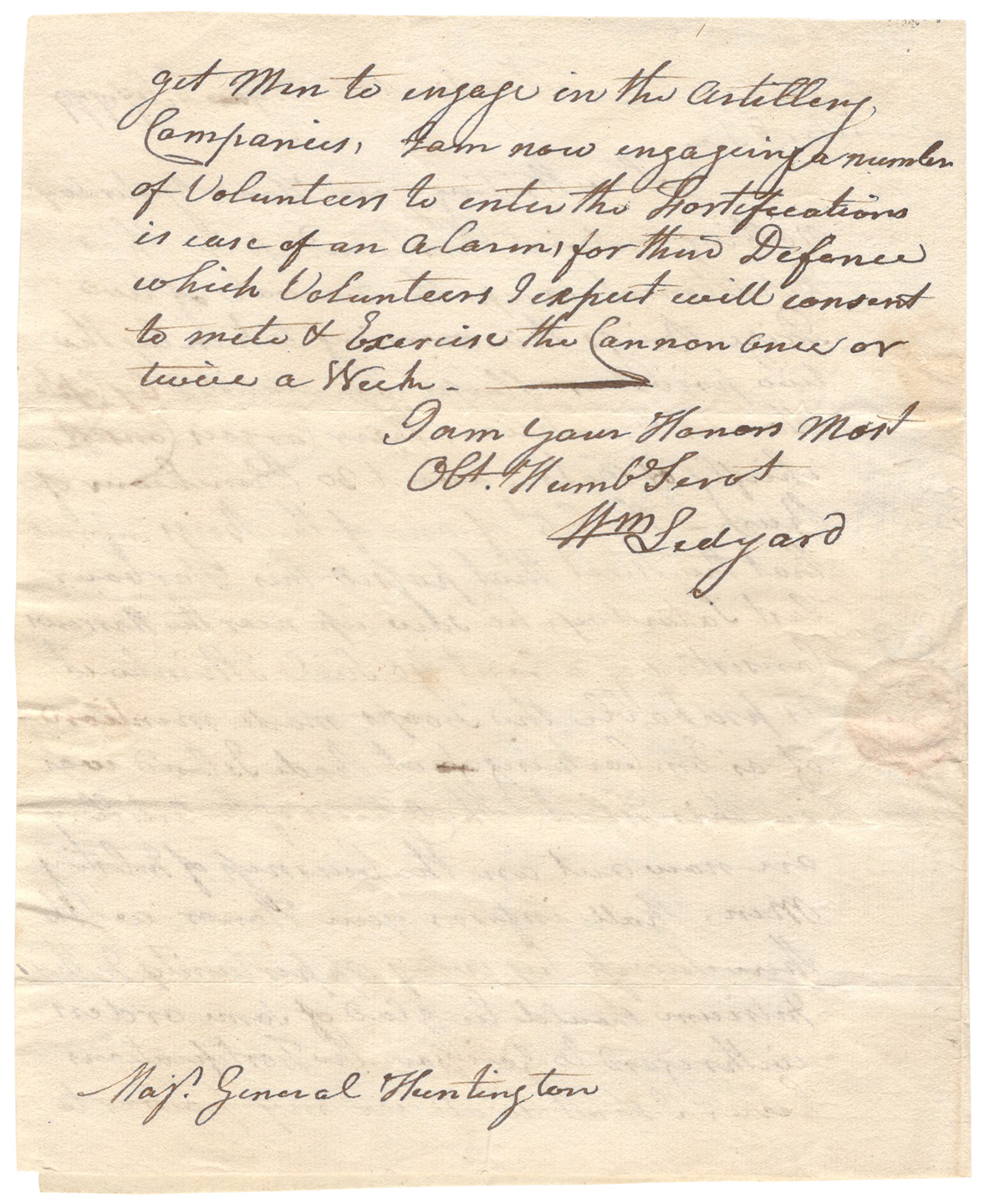

Benedict Arnold, who was busy setting fire to New London across the river, was not present at the Fort Griswold massacre. That did not prevent him from attempting to cover up the crime in his report to Sir Henry Clinton in New York the following morning: “I have inclosed a return of the killed and wounded, by which your excellency will observe that our loss, though very considerable, is short of the enemy’s, who lost most of their officers, among whom was their commander, Col. Ledyard. Eighty-five men were found dead in Fort Griswold, and sixty wounded, most of them mortally. Their loss on the opposite side (New London) must have been considerable, but cannot be ascertained.”3

Benedict Arnold, who was busy setting fire to New London across the river, was not present at the Fort Griswold massacre. That did not prevent him from attempting to cover up the crime in his report to Sir Henry Clinton in New York the following morning: “I have inclosed a return of the killed and wounded, by which your excellency will observe that our loss, though very considerable, is short of the enemy’s, who lost most of their officers, among whom was their commander, Col. Ledyard. Eighty-five men were found dead in Fort Griswold, and sixty wounded, most of them mortally. Their loss on the opposite side (New London) must have been considerable, but cannot be ascertained.”3