William LEDYARD (1738-1781) Connecticut militia officer who commanded Fort Griswold guarding New London, Connecticut. He was tragically killed on 6 September 1781 during Benedict Arnold’s Raid on New London. Although Ledyard ordered his men to lay down their arms when the enemy captured Fort Griswold, the British officer in command killed him with the sword he had offered in surrender—precipitating a massacre of the fort’s eighty defenders.

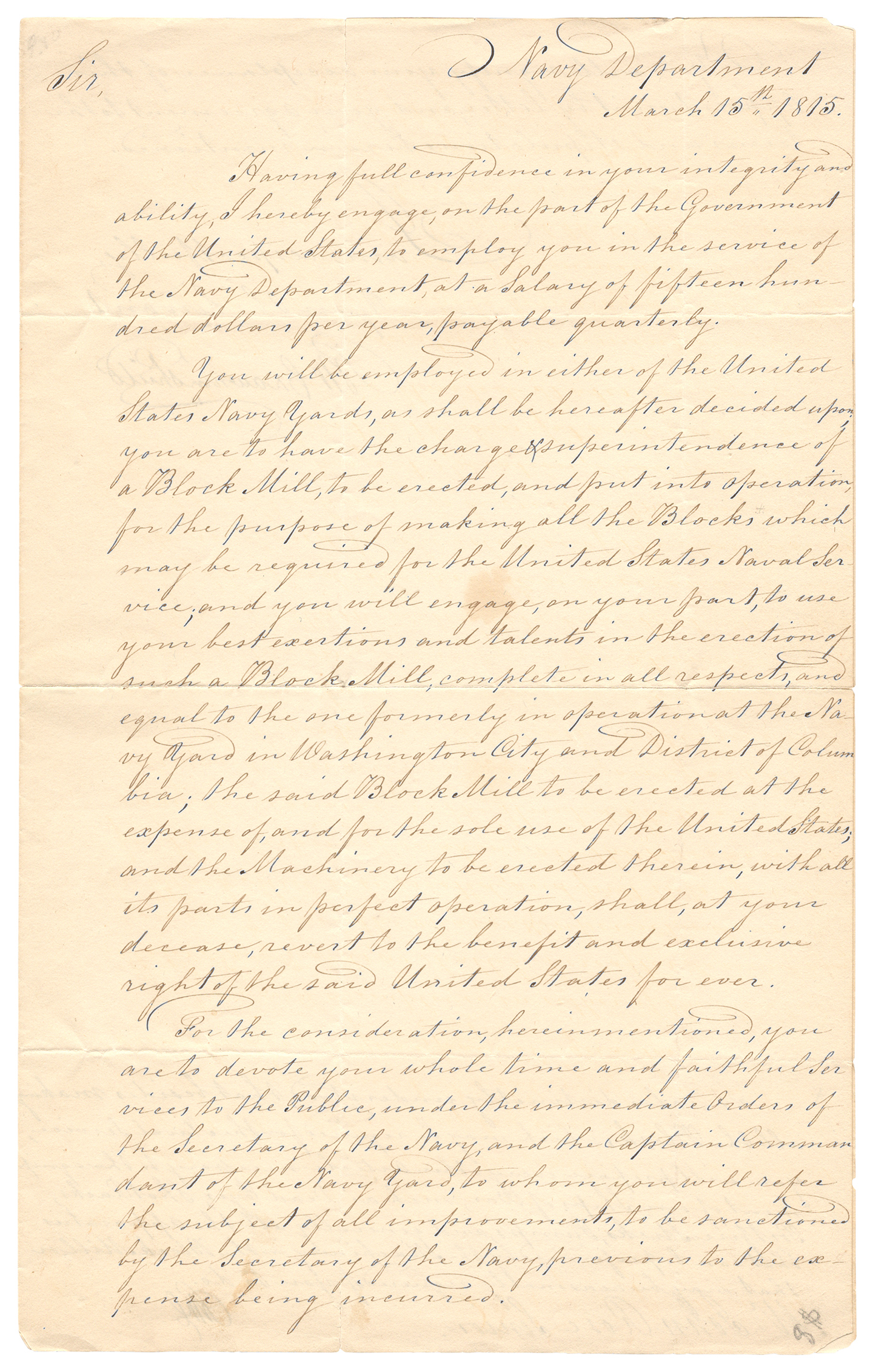

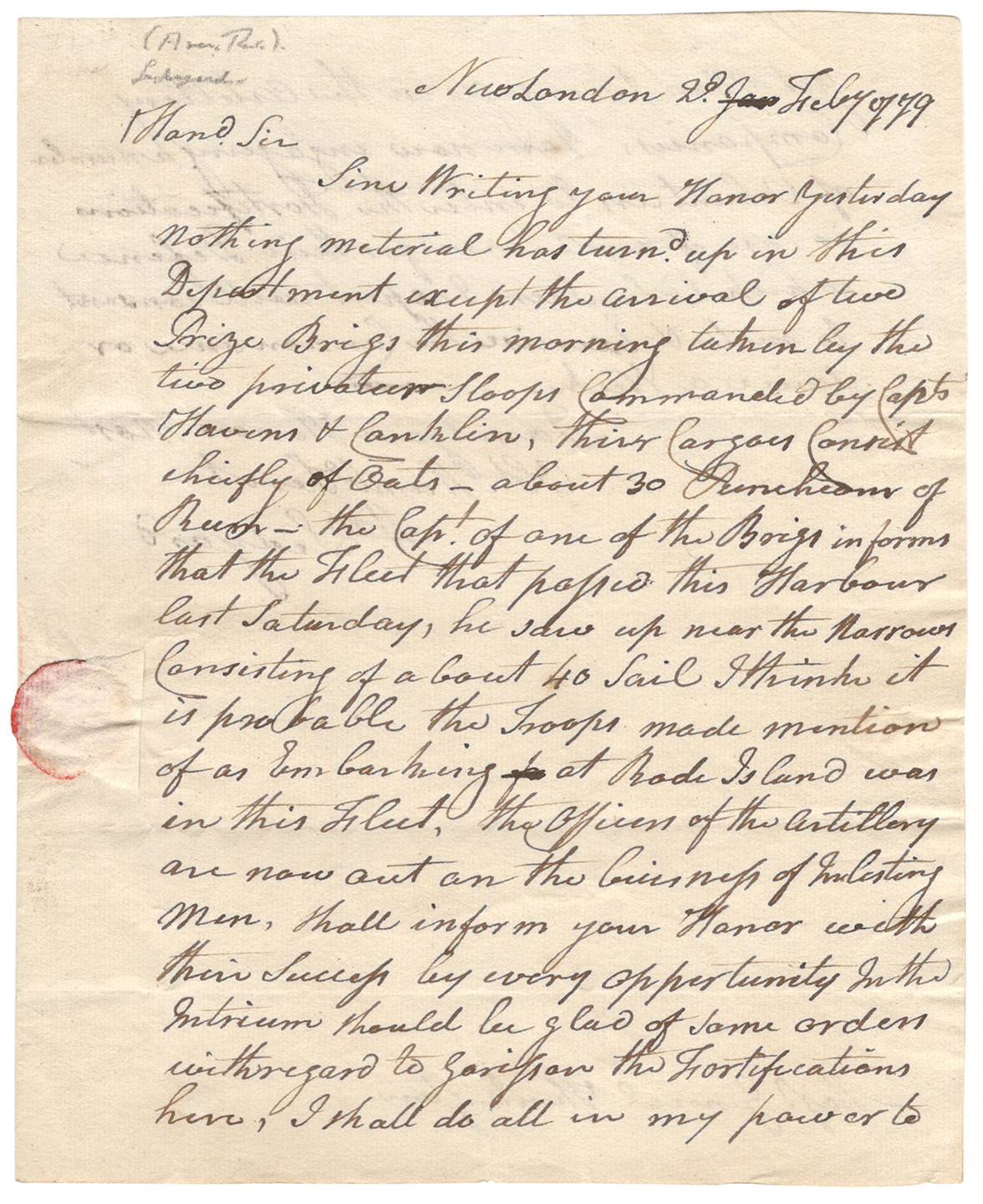

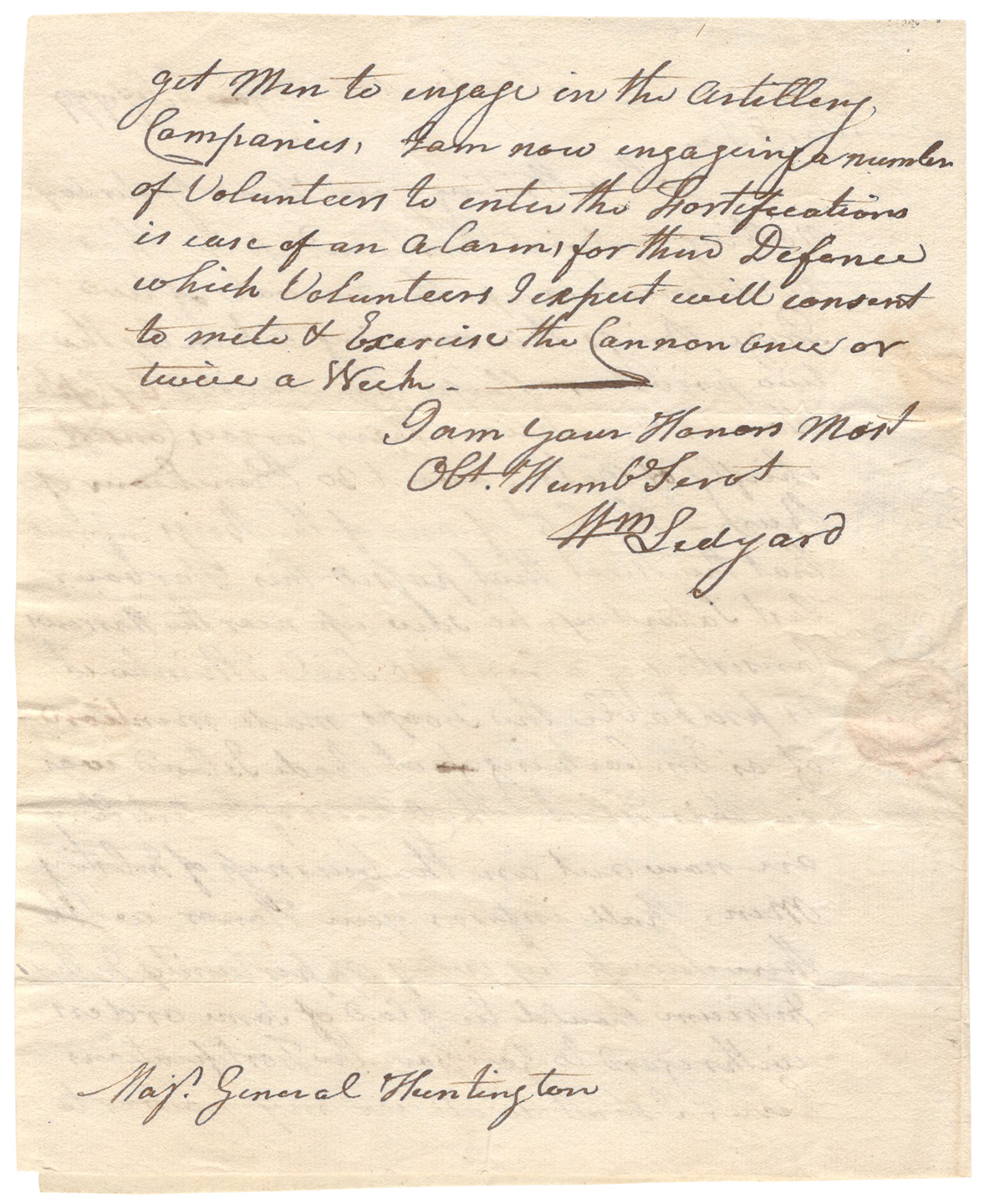

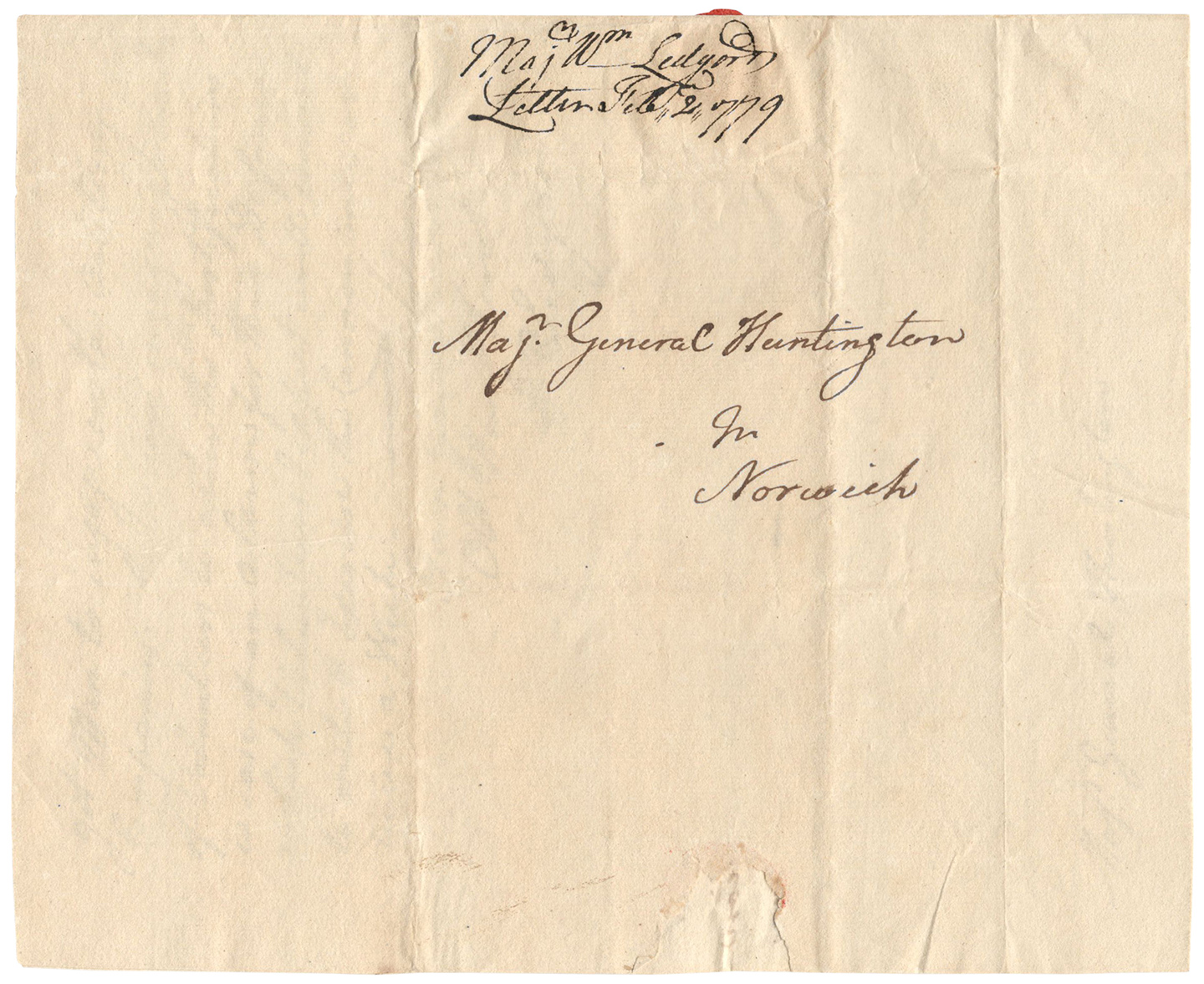

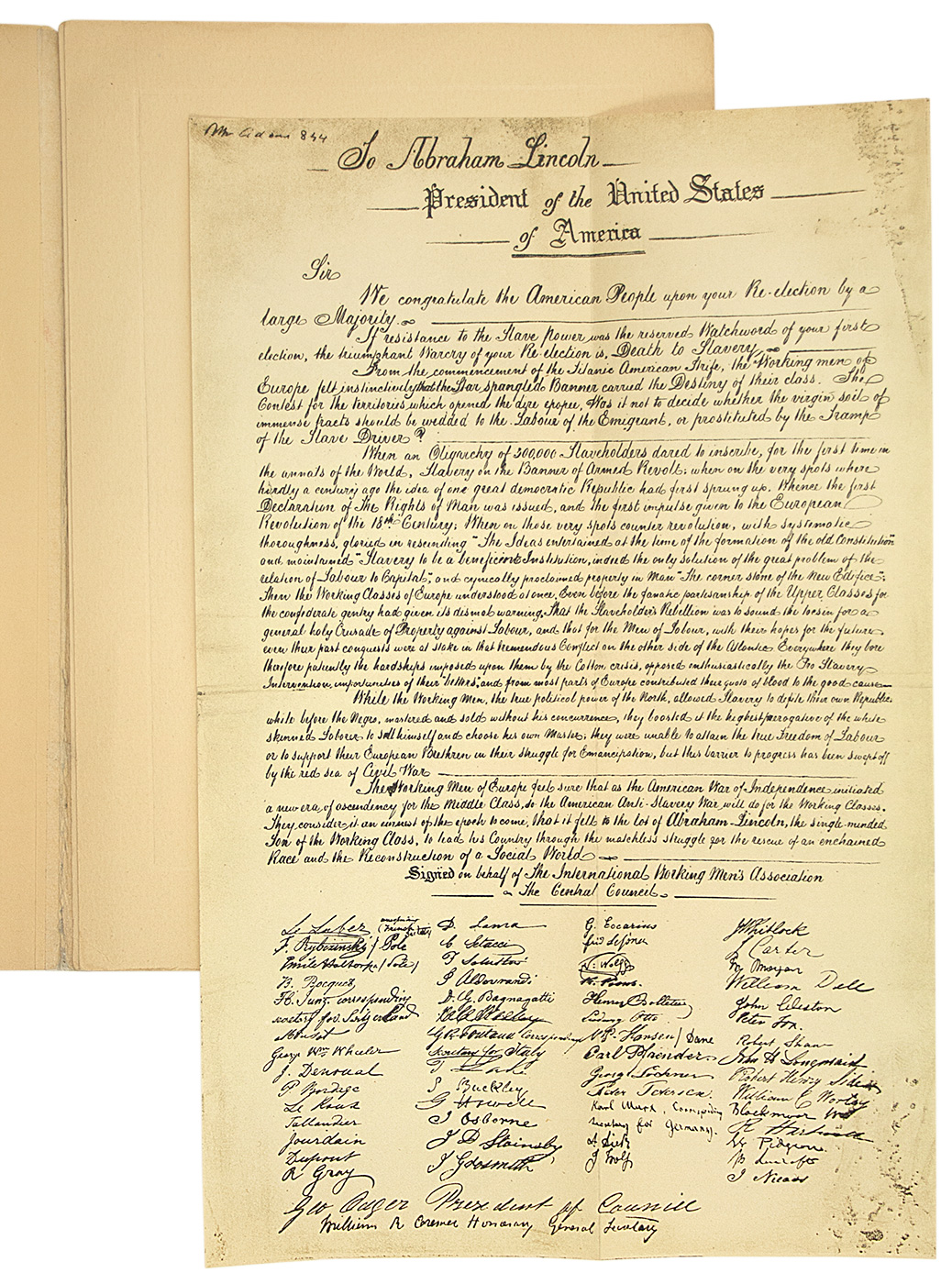

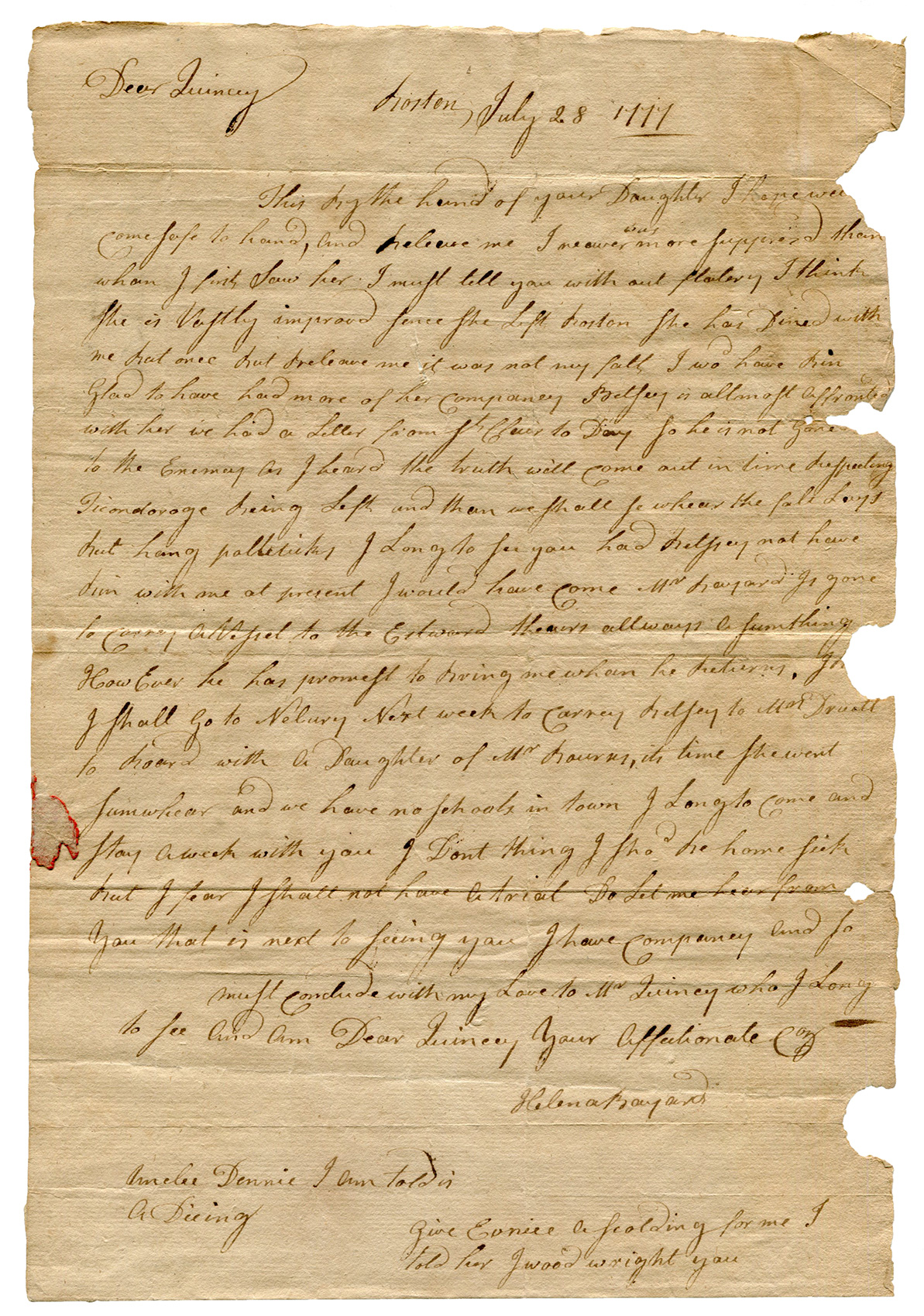

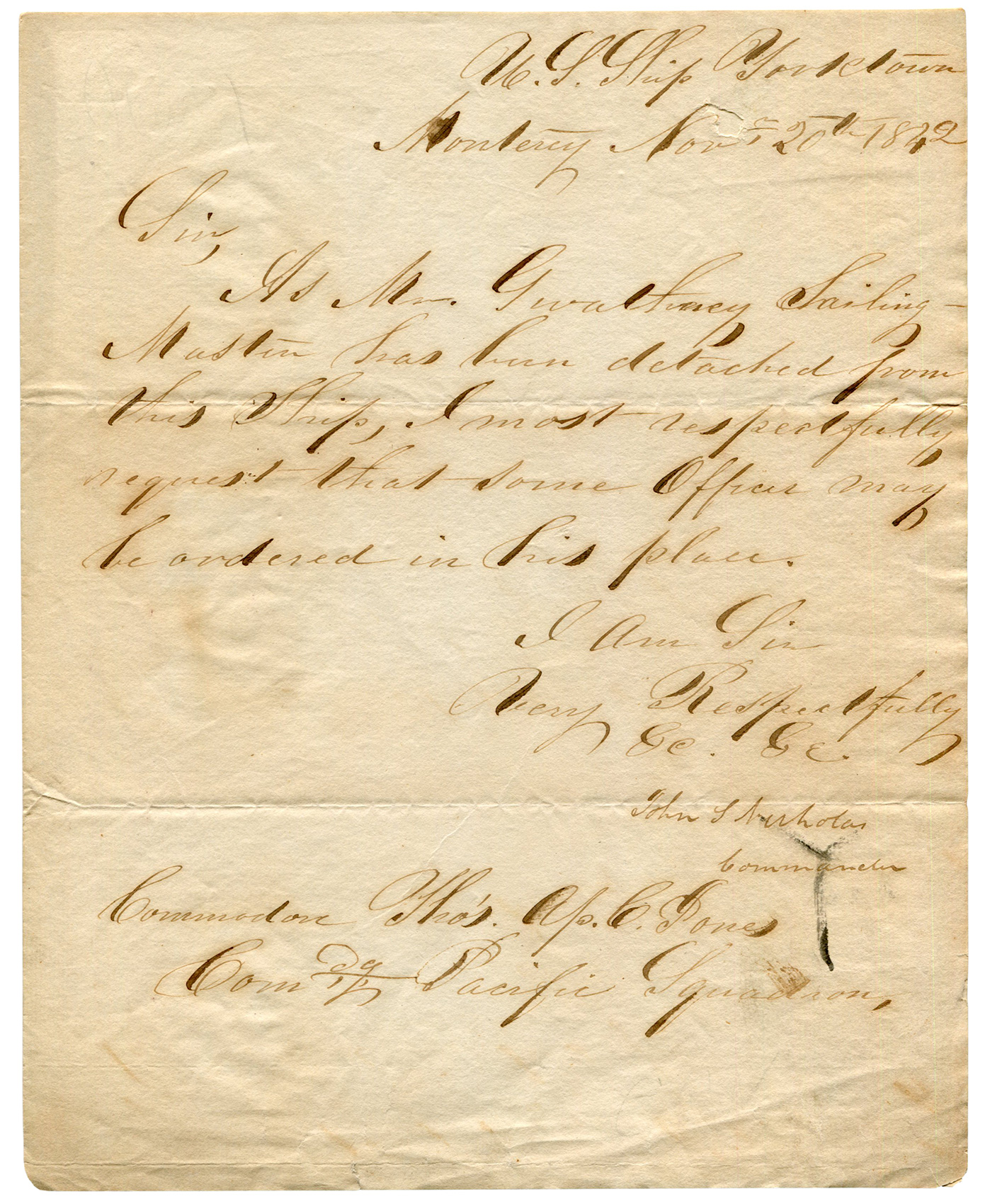

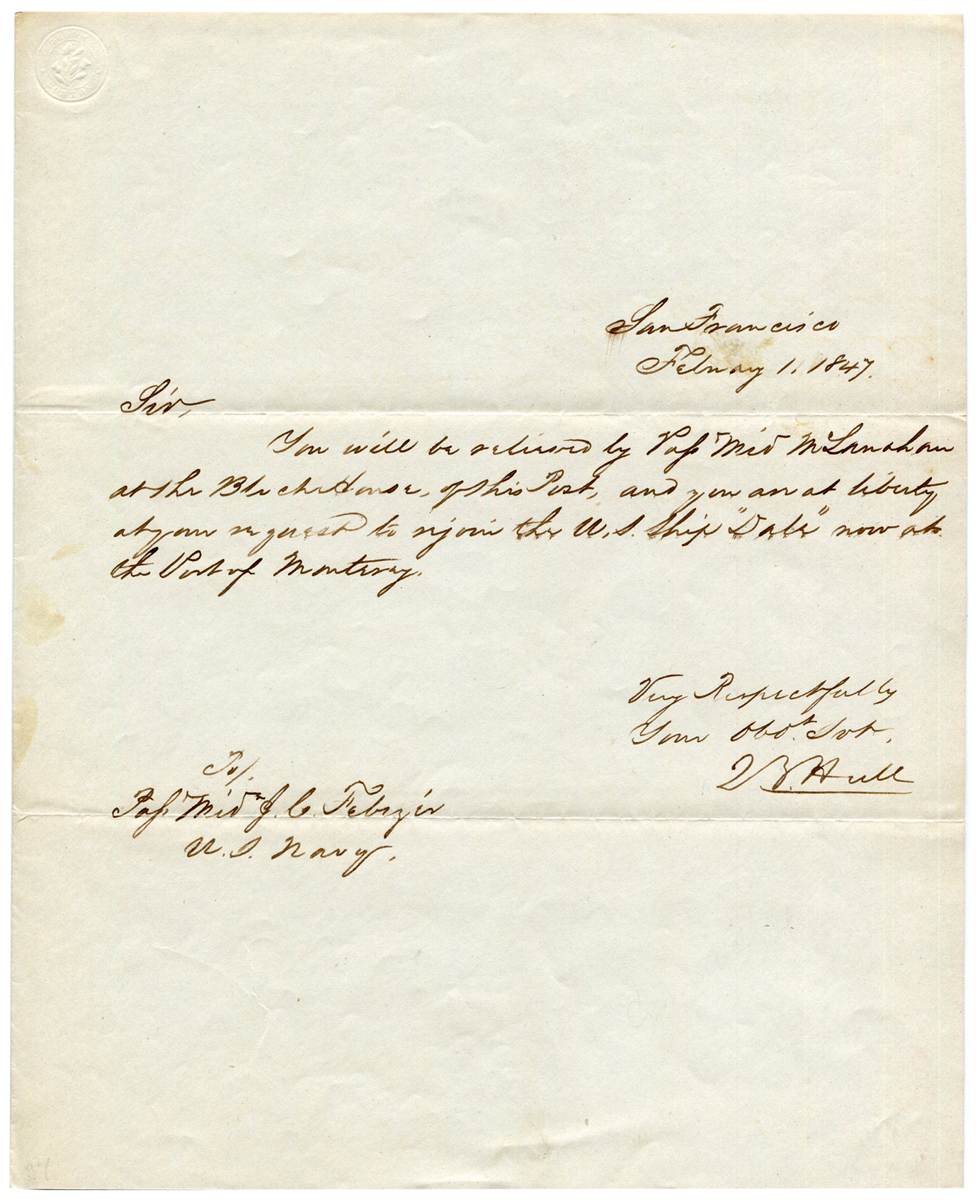

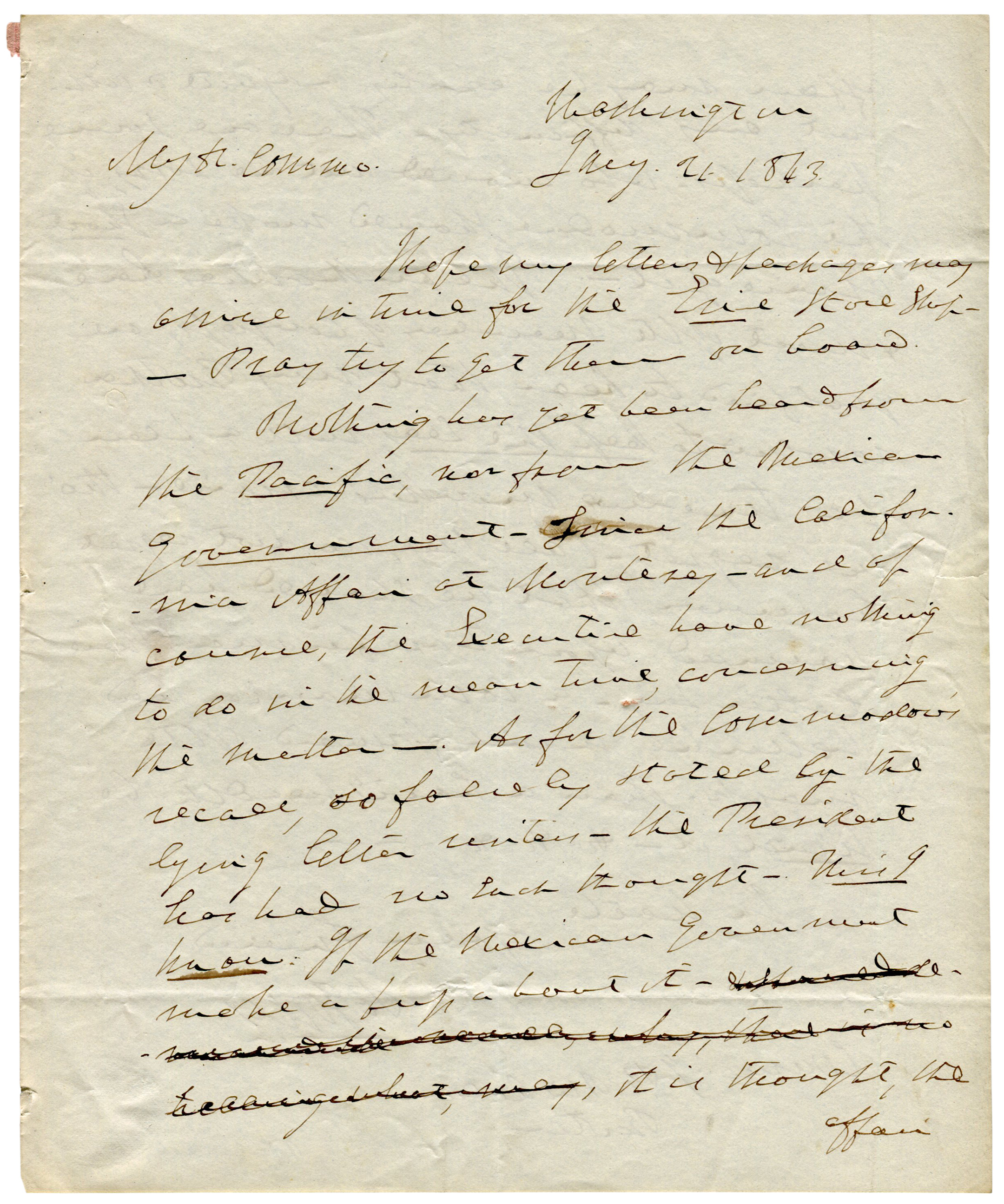

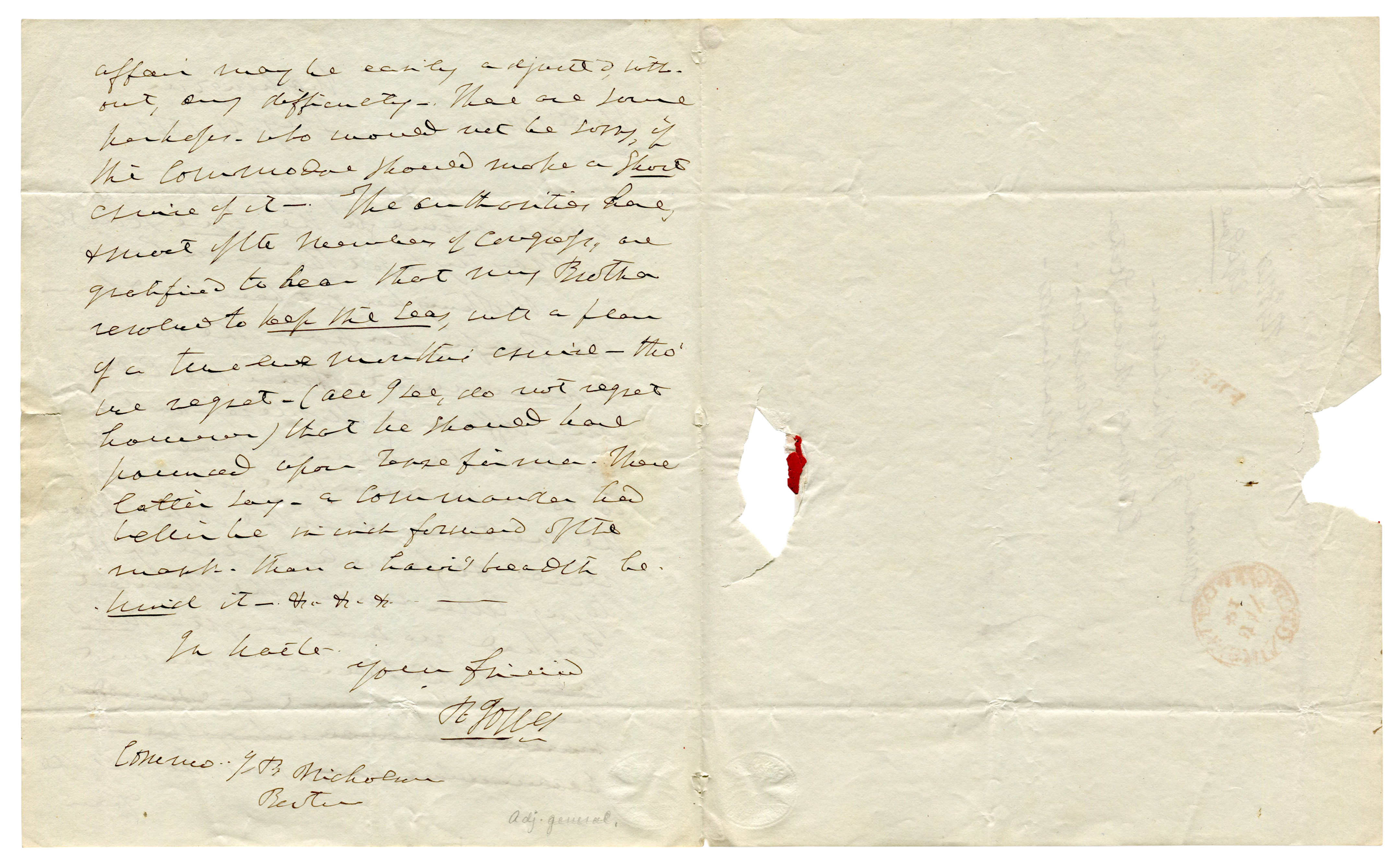

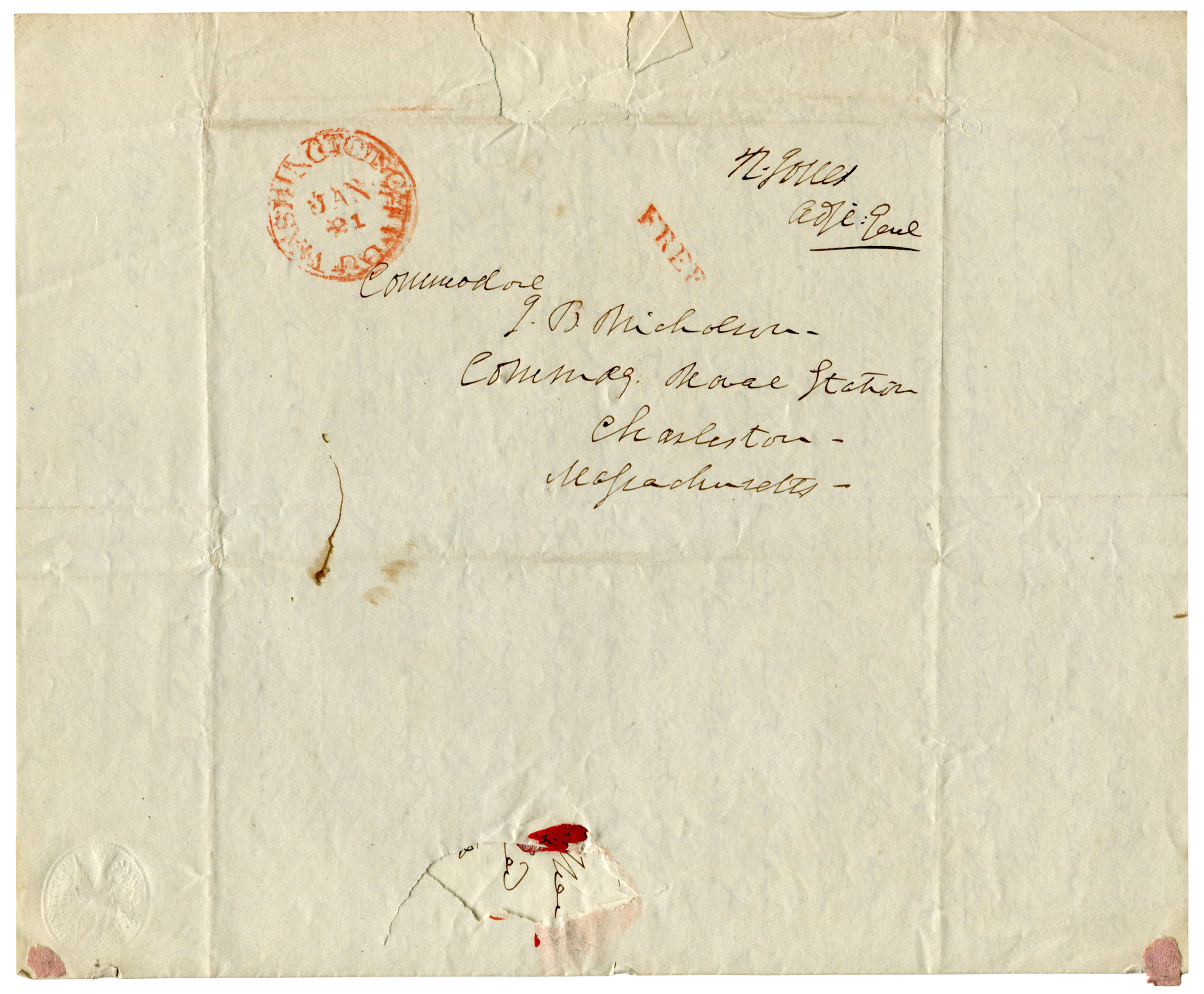

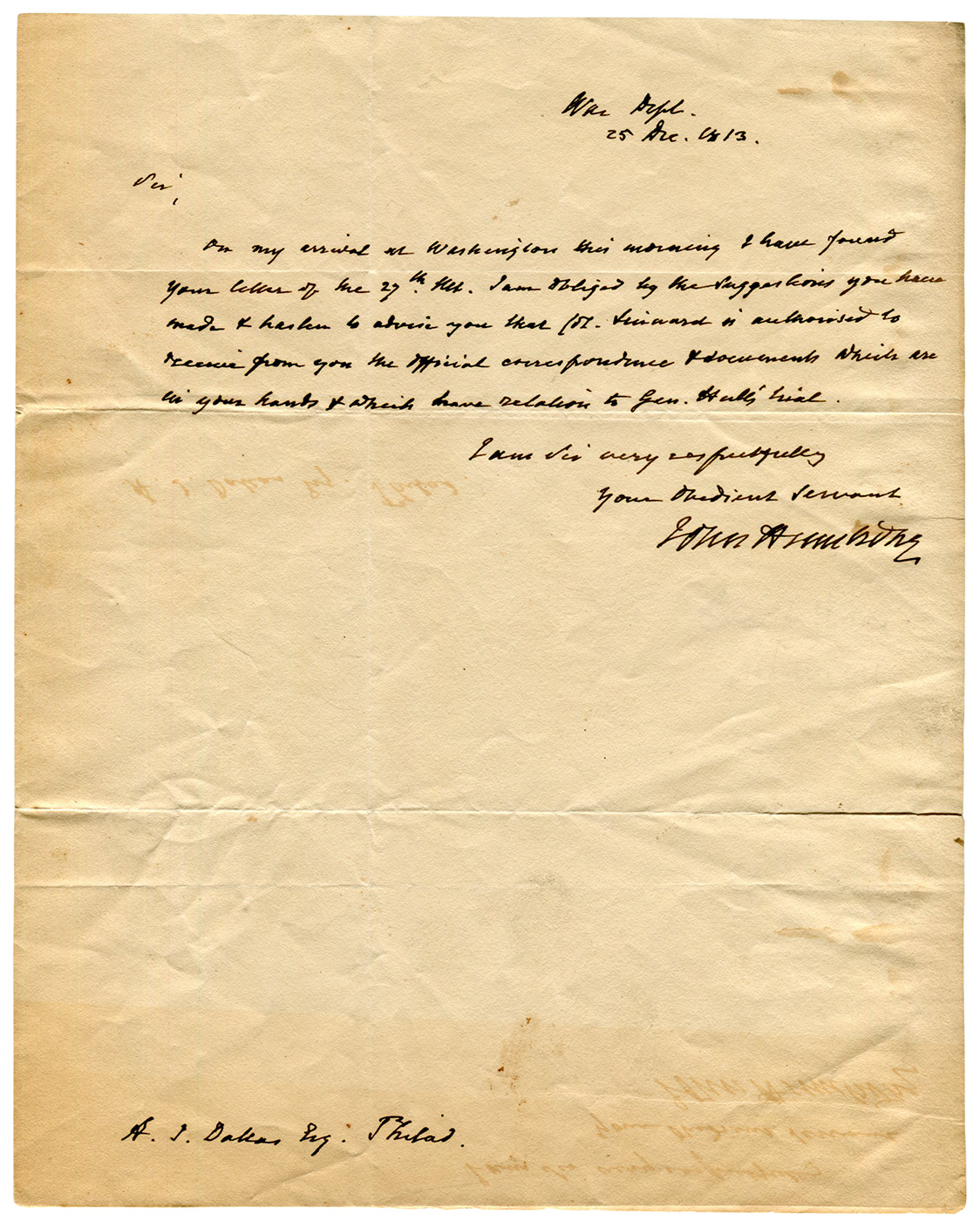

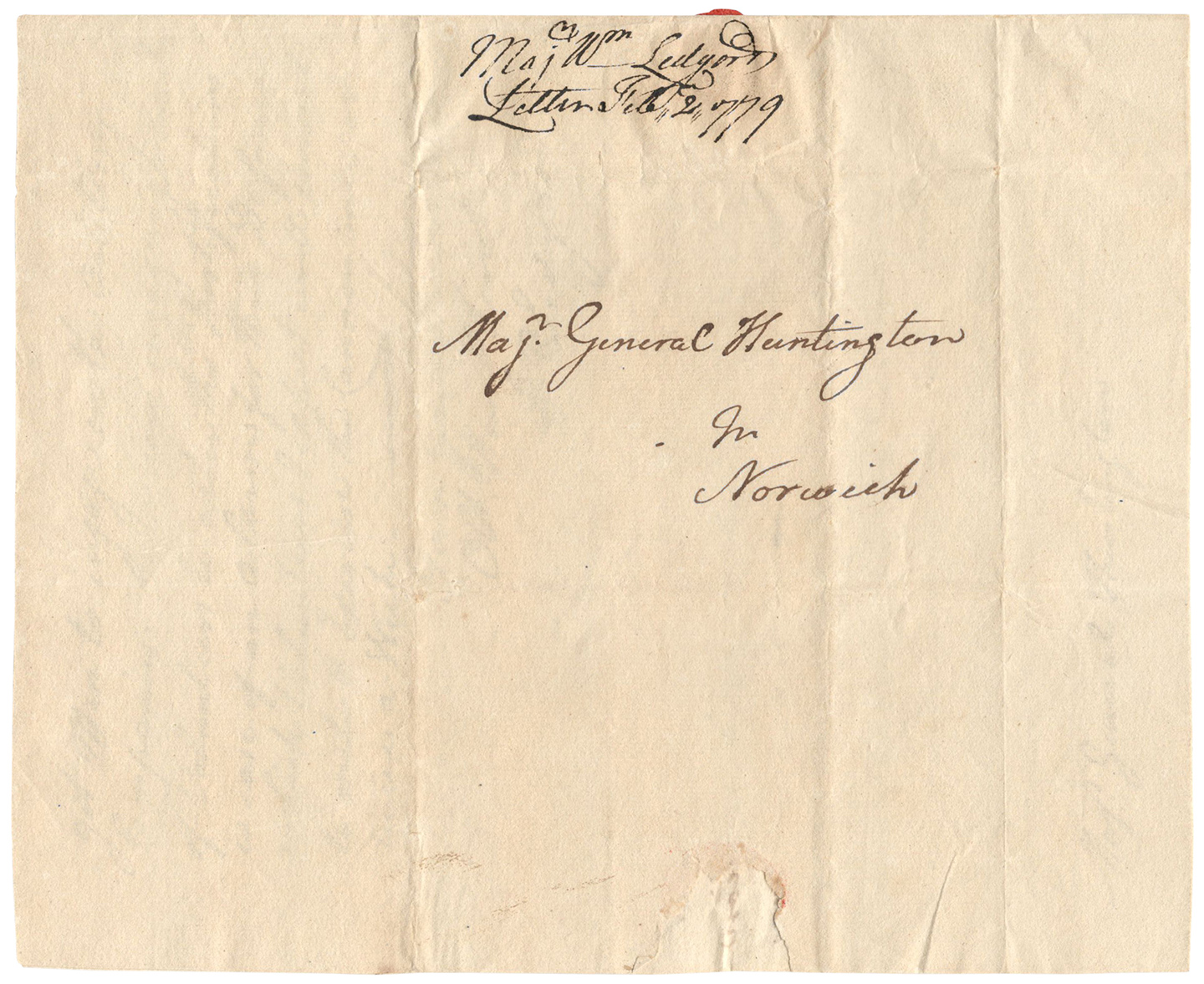

Fine content War date Autograph Letter Signed, “Wm. Led yard” as Lieutenant Colonel, 2pp., 195 x 155 mm. (7 5/8 x 6 1/4 in.), New London [Connecticut], 2 February 1779, addressed in his hand on the integral transmittal leaf to “Maj General [Jabez] Huntingdon In Norwich“. Docketed on verso by Jabez HUNTINGTON (1719-1786). An informative letter, updating his commander on naval affairs, and British moves around Newport, as well as the critical need to recruit artillerymen to reinforce Fort Griswold.

Ledyard opens his letter reporting on the continued success of American privateers operating against British shipping on Long Island Sound: “Since Writing your Honor yesterday nothing material has turn[e]d up in this Department except the arrival of two Prize Brigs this morning taken by the two privateers Sloops Commanded by Capts Havens & Conklin[g], their Cargoes Consist chiefly of Oats — about 30 Puncheons of Rum –” Nearly 3000 imperial gallons of rum and 12,000 bushels of oats bound for British troops stationed in eastern Long Island was the day’s haul for Connecticut privateer sloops Beaver, commanded by Captain Havens and the sloop Eagle, a six gun vessel, led by Captain E. Conkling. The ships they had seized were part of a much larger relief fleet that had arrived in New York from Cork several weeks before, providing much-need supplies to their headquarters in New York and garrisons in Newport and other outposts. The seizure proved to be the end of a productive week for the two Connecticut privateers who had the previous week had taken the Ranger a 12-gun British privateer that had been terrorizing the Long Island Sound for some time. The Connecticut captains had surprised the Ranger at Sag Harbor, and after delivering the brig to New London, again took to the sound where they were forced to take shelter behind Gardiner’s Island after they spotted a large fleet of 20 sail under escort, entering the Sound bound for New York. The next morning they arrived again at Sag Harbor where they found seven of the ships they saw the previous day anchored at Sag Harbor. The However the Connecticut brig, Middletown, which had accompanied the Beaver and Eagle, became stuck on a shoal and became an easy target for the British armed brig protecting the other vessels. After about 4 or 5 hours, the crew of the Middletown was forced to abandon ship. The other two Connecticut vessels took on them on and left the area only to happen upon the two aforementioned British brigs hauling oats and rum—a worthy consolation prize.1

Ledyard also chronicles the beginning of the end of the British occupation of Newport—a post that had been under severe stress for want of supplies following the American attempt wrest control of the town the previous year at the Battle of Rhode Island. He reports the observation of “… the Capt. of one of the Brigs in forms that the Fleet that passed this Harbour last Saturday, he saw up near the Narrows Consisting of about 40 Sail I think it probable the Troops made mention of as Embarking at R[h]ode Island was in this Fleet…” A contemporary newspaper account corroborates Ledyard’s suspicions: a man who crossed the British lines from New York around 2 February reported that an entire brigade had arrived in the city from Newport—which would correspond to timing of Ledyard’s report2. Only a month before, a British expeditionary force of 3,500, drawn from Sir Henry Clinton’s main army in New York, had taken Savannah, Georgia. Now, seeking to take Charleston, South Carolina as well, he required reinforcements—enough so to make the continued occupation of Newport impracticable. By October 1779, they had abandoned the Rhode Island town for good. Ledyard’s report of the troop embarkation from Newport appears to be the beginning of Clinton’s drawing-down process.

While Ledyard surely welcomed prospect of the end of British control of Newport, that alone would not end British threats to the Connecticut coast. He moves on to the subject of reinforcing Fort Griswold, a critical defense for the town of New London, and the place he would meet his fate in 1781: “… the Officers of the Artillery are now out on the business of Inlisting Men, shall inform your Honor with their Success by every opportunity In the Interum should bee glad of some orders with regard to Garrison the Fortifications here, I shall do all in my power to get Men to engage in the Artillery Companies, I am now engaging a number of Volunteers to enter the Fortifications is case of an alarm, for their Defence which Volunteers I expect will consent to mete & Exercise the Cannon once or twice a week.—”

Although Fort Griswold, situated on the eastern bank of the Thames River opposite New London, commanded a strong position, it’s secrets were betrayed by Benedict Arnold, who, in September 1781, led a raid on New London, burning much of the strategically-important Connecticut seaport. Arnold, having an intimate knowledge of the Fort’s layout and firing angles, managed steer the British fleet clear of its guns. A detachment of 600 redcoats, led by Lieutenant Colonel Eyre, landed on the eastern bank of the Thames and surrounded Fort Griswold, demanding its surrender. Ledyard refused, and the British attacked the Fort, defended by less than 160 poorly-trained militiamen. Despite the odds, Ledyard’s men defended it for at least an hour, mortally wounding Colonel Eyre during the action. Command devolved to Major Montgomery, who was, in turn, killed while mounting the parapet.

Next in command was Major Bromfield, a Loyalist, who managed to breach the entrance and led the troops into the fort’s interior. When he entered the fort, he demanded to know who had been in charge. Ledyard reportedly responded, “I did sir, but you do now,” and offered his sword in surrender. Bromfield took the sword and stabbed Ledyard to death with it, which set off a massacre of about 80 of the fort’s now defenseless defenders.

Benedict Arnold, who was busy setting fire to New London across the river, was not present at the Fort Griswold massacre. That did not prevent him from attempting to cover up the crime in his report to Sir Henry Clinton in New York the following morning: “I have inclosed a return of the killed and wounded, by which your excellency will observe that our loss, though very considerable, is short of the enemy’s, who lost most of their officers, among whom was their commander, Col. Ledyard. Eighty-five men were found dead in Fort Griswold, and sixty wounded, most of them mortally. Their loss on the opposite side (New London) must have been considerable, but cannot be ascertained.”3

Benedict Arnold, who was busy setting fire to New London across the river, was not present at the Fort Griswold massacre. That did not prevent him from attempting to cover up the crime in his report to Sir Henry Clinton in New York the following morning: “I have inclosed a return of the killed and wounded, by which your excellency will observe that our loss, though very considerable, is short of the enemy’s, who lost most of their officers, among whom was their commander, Col. Ledyard. Eighty-five men were found dead in Fort Griswold, and sixty wounded, most of them mortally. Their loss on the opposite side (New London) must have been considerable, but cannot be ascertained.”3

A superb military-content letter, by an important officer, tragically killed in action.

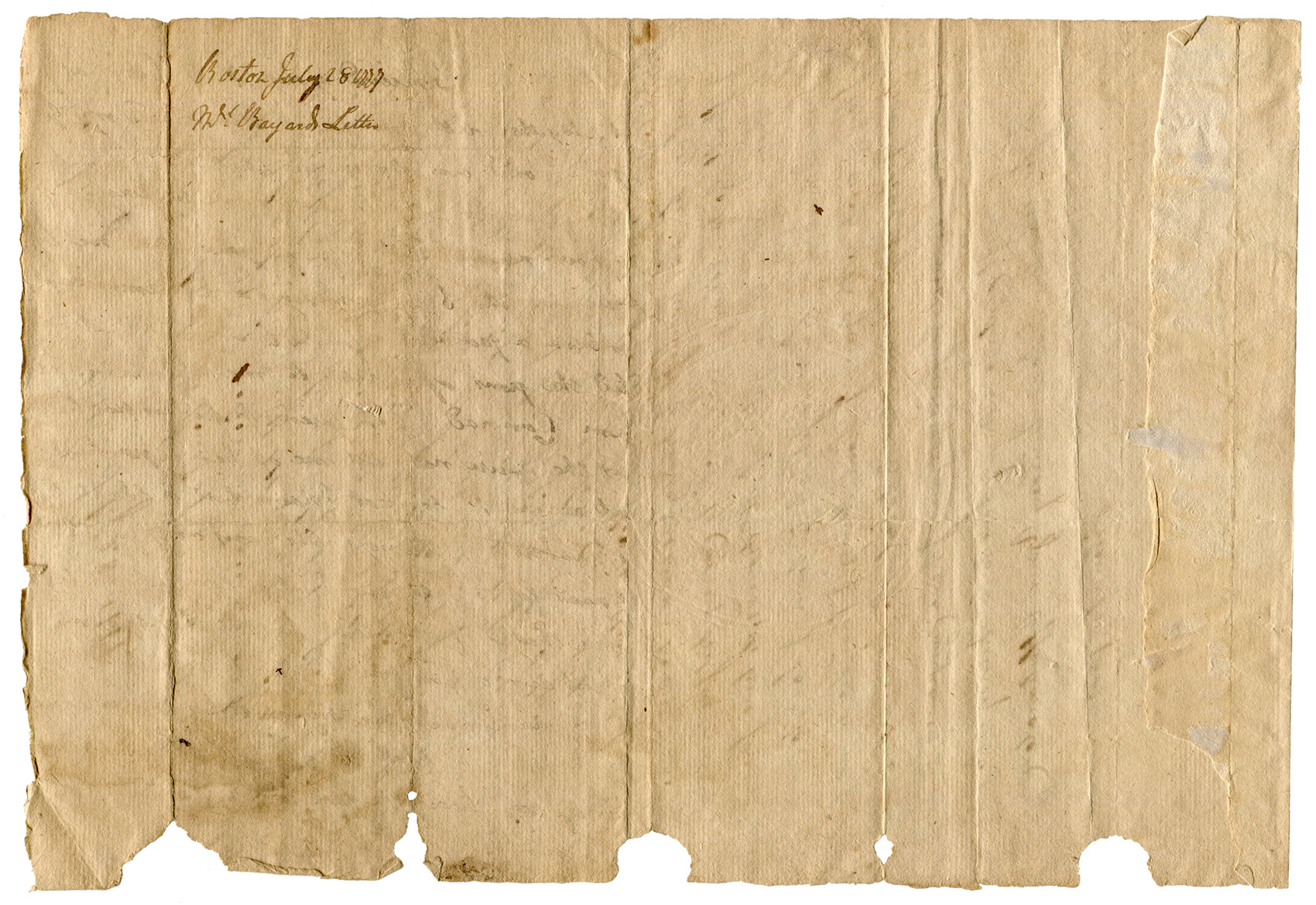

Expected mailing folds, minor loss to integral transmittal leaf from seal tear well clear of any text, else quite clean and bright and in very fine condition.

(EXA 6000) SOLD.

_________

1 Connecticut Journal, New Haven, 10 Feb. 1779, 3.

2 Exeter Journal (N.H.), 23 Feb. 1779, 3.

3 “Ledyard, William, “Appleton’s Cyclopædeia of American Biography, 1892 ed.

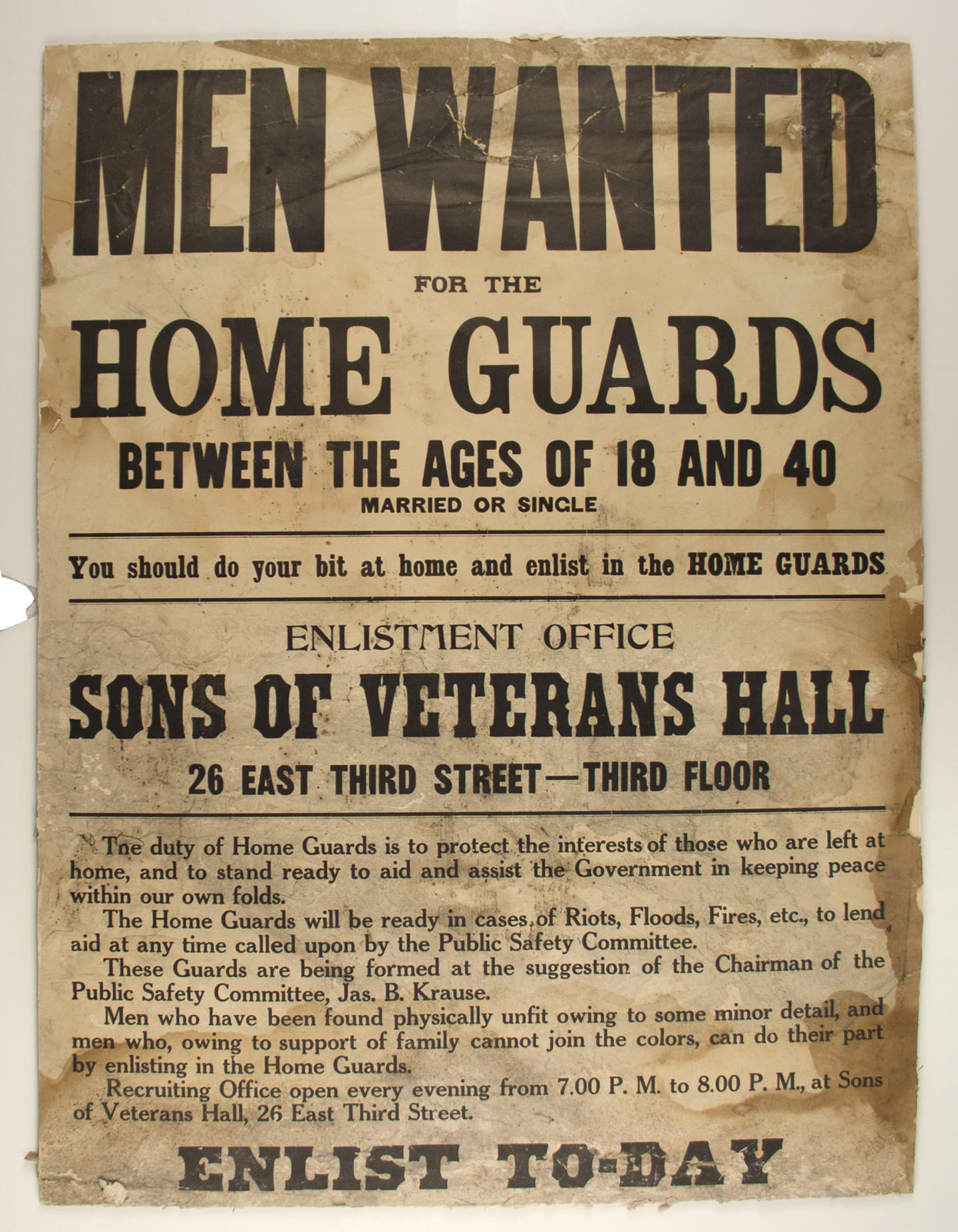

(First World War) Rare Broadside, MEN WANTED FOR THE MOME GAURDS BDETGWEEN THE AGES OF 18 AND 40 MARRIED OR SINGLE… ([Williamsport, Penn?: 1917], [SIZE].

(First World War) Rare Broadside, MEN WANTED FOR THE MOME GAURDS BDETGWEEN THE AGES OF 18 AND 40 MARRIED OR SINGLE… ([Williamsport, Penn?: 1917], [SIZE].