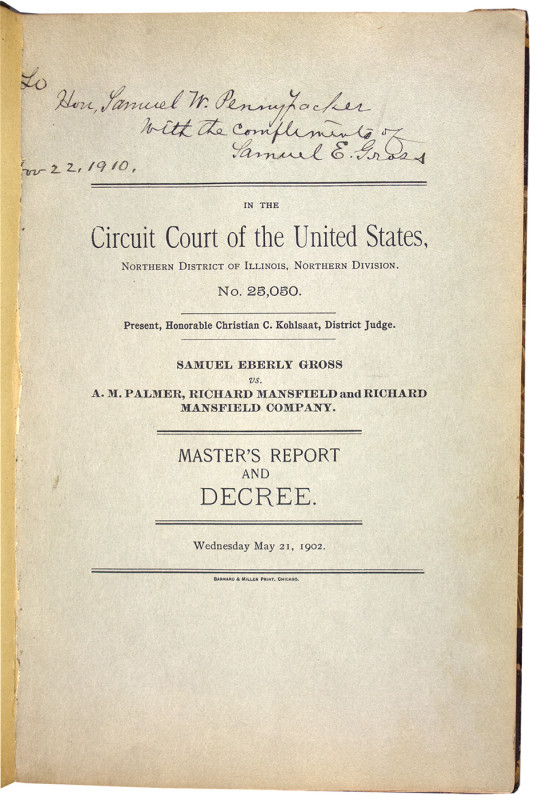

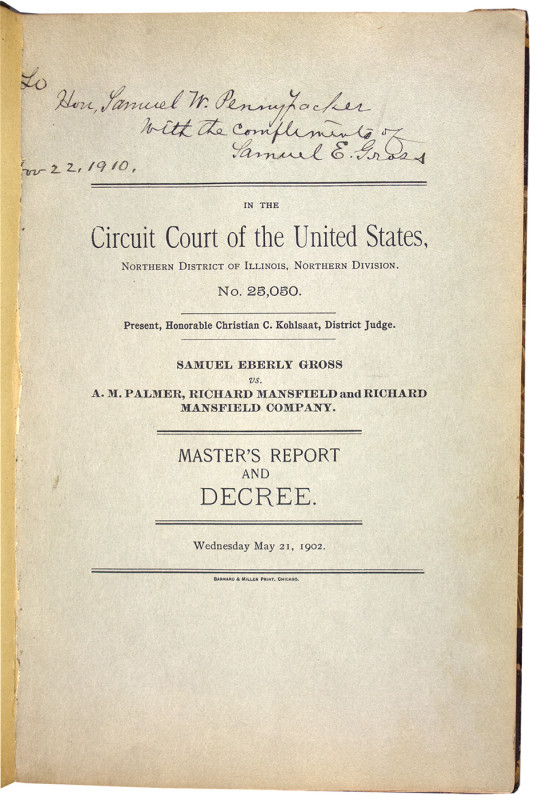

Samuel Eberly GROSS (1843 – 1913) Signed book: In the Circuit Court of the United States, Northern District of Illinois, Northern Division. No. 23,030. – Present, Honorable Christian C. Kohlsaat, District Judge. – Samuel Eberly Gross vs. A. M. Palmer, Richard Mansfield, and Richard Mansfield company. – MASTER’S REPORT AND DECREE. – Wednesday, 21 May 1902. (Chicago: Bernard & Miller, [1902]), 68pp. with several blank leaves at end bearing newspaper reports on the case. In original titled wraps bound in three-quarter leather marbled boards. Signed and inscribed by Gross on the original titled paper wrap, “To Hon. Samuel W. Pennypacker with the compliments of Samuel E. Gross Nov. 22, 1910.”1

On 28 December 1897 Edmond Rostrand premiered his new play, Cyrano de Bergerac in Paris to mass critical acclaim. Clayton Hamilton, the American drama critic declared, “No other play in history, before or since, has ever attained the popular success so instantaneous and so enormous.” Meanwhile in Chicago, Samuel Eberly Gross, a successful real estate developer cried foul. Asserting that Rostrand’s hit play bore a strong resemblance to his own published drama, The Merchant Prince of Cornville and specifically, the climatic balcony scene where Cyrano woos his love secretly feeding lines to another man while hidden in the bushes.

Gross claimed he had submitted his own play to the same Paris theater where Rostrand first presented Cyrano, but it had been rejected. Noting that Rostrand had the “run of the theater reading room” at the time, Gross concluded that the prolific French playwright had lifted the scene for inclusion in his own work. Although in reality, Gross’ claim was almost completely spurious, he managed to halt a Chicago production of Cyrano through a court injunction. Federal Judge Christian C. Kohlsaat ordered a special master, E. B. Sherman to sift through the evidence and submitting a report with recommendations for review by the court. Sherman concluded in his report that Gross had indeed been plagiarized by Rostrand, not only due to the signature balcony scene but in thirty other instances. Judge Kohlsaat upheld Sherman’ opinion and awarded Gross a token one dollar in damages – together with an order prohibiting the staging of Cyrano de Bergerac in the United States.

The case became a sensation in the press. In the wake of the verdict, New York Times published an excerpt from The Merchant Prince balcony scene ostensibly for “the reader to decide,” yet the snide tone of the article betrayed their true belief that the ruling was completely ludicrous. When asked about the verdict, Rostrand quipped: “I am ready to admit I took … all our 17th century history from Eberle Gross of Chicago, and, in order to end the matter once and for all, I confess I stole Les Romanesques from Smithson of Jefferson City, Mo.; La Princesse Lointaine, from Giles Trumbull of Columbus, Ohio; L’Aiglon from Tom Sambo of Springfield, Illinois; and that I drew the idea of La Samarataine from the apocryphal gospel of the Rev. Hon. Augustus Wonnacott of Hartford, Conn. I add that I am negotiating, at the present moment, with a Virginia planter for the purchase of a manuscript, and that I have just purloined from the house of a Louisiana shipowner a great piece on Joan of Arc, the Maid of New Orleans.”

Ironically, Gross should have asked for more than a token $1 in damages as he nearly bankrupted himself in his long quest for recognition. Although he made over $3,000,000 building suburban homes in the 1890s, at the time of his death in 1913, he was worth a mere $150,000.

In 1920 a federal judge in New York ruled against Gross’ widow and declared Rostand the true author of Cyrano. This is a rare memento from Gross’ quixotic quest for vindication.

Pages overall quite clean, outer boards rubbed and scratched, else very good.

(EXA 4320) $2,000

____________

1 (1843 – 1916) Pennypacker, the 23rd Governor of Pennsylvania, was also a voracious collector.