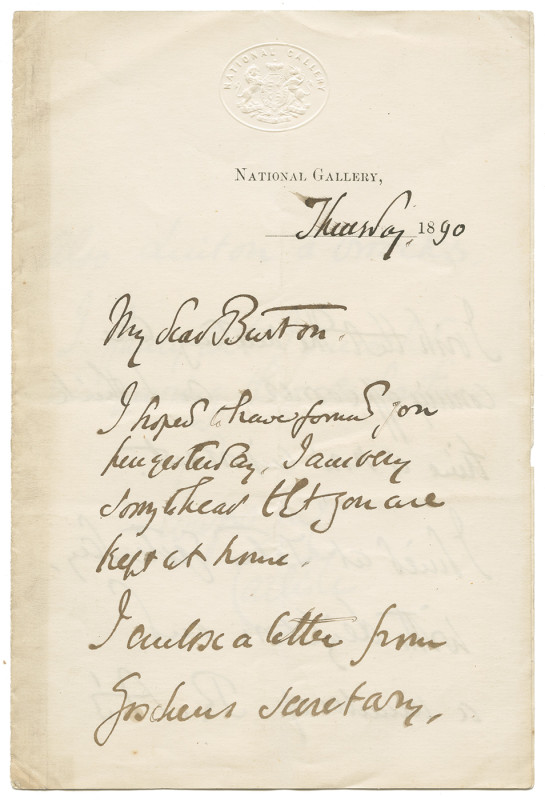

George HOWARD, 9th Earl of Carlisle (1843-1911), British politician and painter, trustee of the National Gallery. An aristocrat and established figure in pre-Raphaelite circles, he was educated at Eton and Cambridge, studying under famous artists Alphonse Legros and Giovanni Costa. He married Rosalind Frances Howard (1845-1921), known as “The Radical Countess” for her liberal politics and passionate participation in the women’s suffrage and temperance movements. Howard served as a Liberal Party Member of Parliament from 1879-1880, and again from 1881-1885. He became an Earl upon the death of his Uncle in 1889.

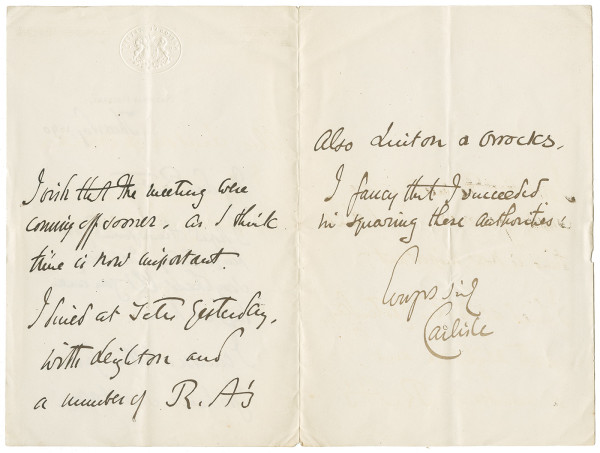

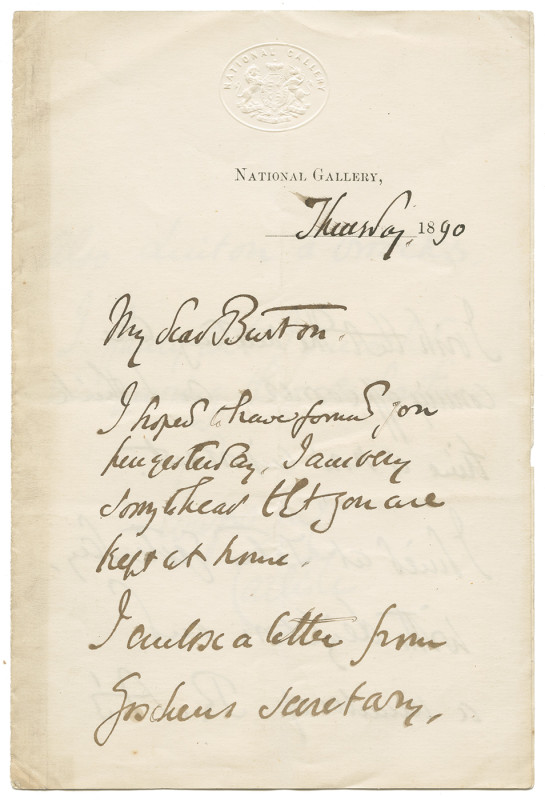

Superb content Autograph Letter Signed “Carlisle” 3pp. 185 x 125 mm., on blind-embossed National Gallery stationary, [London] “Thursday [July?], 1890” to National Gallery Director, Sir Frederic William Burton (1816 – 1900), the third director of the National Gallery concerning his belief that he had lined up support for his plan to house the large gift of British art offered to the nation by sugar magnate Henry Tate (1819 – 1899). Carlisle writes: “I hope to have found you here yesterday, I am very sorry to hear that you are kept at home. I enclose a letter from [Chancellor of the Exchequer, Geroge] Goschen’s secretar y. I wish that the meeting were coming off sooner, as I think time is now important. I dined at [Henry] Tate’s yesterday with [Sir Frederick] Leighton and a member of R[oyal].A[cademy]’s. Also [Sir James] Linton & [James] Orrocks [sic]. I fancy that I succeeded in squaring these authorities.”

On 23 October 1889 sugar magnate and art collector Henry Tate offered his collection of modern British artworks to the National Gallery. Tate’s gift to the nation intensified an ongoing debate in the press and the art world on the place of British art at the National Gallery. For years, art critics had bemoaned the lack of British artwork (especially modern works by living artists) at the National Gallery. One practical issue was the lack of space at the Trafalgar Square facility, and proposals for a new museum for modern British works modeled on the Luxembourg in Paris had been floated for some time. Tate’s generous offer added urgency to the need to find a new home for British art.

On 23 October 1889 sugar magnate and art collector Henry Tate offered his collection of modern British artworks to the National Gallery. Tate’s gift to the nation intensified an ongoing debate in the press and the art world on the place of British art at the National Gallery. For years, art critics had bemoaned the lack of British artwork (especially modern works by living artists) at the National Gallery. One practical issue was the lack of space at the Trafalgar Square facility, and proposals for a new museum for modern British works modeled on the Luxembourg in Paris had been floated for some time. Tate’s generous offer added urgency to the need to find a new home for British art.

Apart from arguments in the press over the scope of the proposed museum (e.g. only modern British art, vs. all British art), locating a suitable facility proved a vexing challenge. Some had proposed Kensington Palace while others advocated a new facility located near Trafalgar Square. Carlisle, a powerful member of the National Gallery, sent a memorandum to the British Government proposing a scheme to utilize the East and West Galleries of the recently-built Imperial Institute in South Kensington. According to an article in the August 1890 issue of The British Architect, “On July 24th last he called together at the Privy Council Office gentlemen whose names would, he thought commend themselves to their lordships. He was there with the Chancellor of the Exchequer, and they had with them Sir Henry Layard, Sir Frederick Leighton. Sir F. Bur ton, Sir John Gilbert, and Sir James Linton, so that their lordships would see it was a very respectable assembly of persons well qualified to judge of this question … Considerable discussion took place with respect to the eastern and western galleries…”1 It was determined that the galleries were the best suited for the purpose and a second meeting took place to tour the galleries a few days later to confirm the opinion. The reaction in the press was generally negative. The British Architect derided the plan as proof that “…our Government is a delighter in make-shifts…” and thought it more fitting to construct a facility specifically designed to the purpose.2 The editors at Truth went a step further and derided the motives of Carlisle: “Who cannot read between the lines? Who cannot perceive how the whole thing was ‘worked’ at the Privy Council Office? Who cannot guess at the preliminary smoothing down of these gentlemen before they met there? Who cannot imagine how Lord Cranbrook was first got at by the Imperial Institute people? Who cannot picture to himself Mr. Goschen’s oily concurrence in the proposal, as though he had never before hear of it. Who cannot appreciate Sir Frederick Lighton’s contribution to the discussion? Who does not smile at the thought of a ‘certain number’ going through the farce of inspecting the galleries?”3

Carlisle’s proposal foundered in the press and in public opinion. The painter James Orrock (1829 – 1913) defended the proposal given in November 1890 but the idea did not gain traction. Prominent figures in the art world continued to quibble over a suitable home until Tate withdrew his offer in March 1892. It was this move that forced a compromise. In November 1892, William Harcourt, the new Chancellor of the Exchequer, proposed building the new gallery at Millbank on the Thames where the present Tate Gallery (completed in 1897) now stands.4

Usual folds, usual folds, light toning at margins, minor marginal chip to back leaf, else very good condition.

(EXA 4024) $450

______________________

1 The British Architect, (22 Aug. 1890), 125.

2 Ibid.

3 As quoted in Amy Woodson-Boulton, “The Art of Compromise: The Founding of the National Gallery of British Art, 1890 – 1892” Museum and Society (Nov. 2003), 157.

4 Ibid., 160.