Jonathan HARRINGTON (1758-1854) The last surviving member of John Parker’s company at the Battle of Lexington on 19 April 1775, serving as the fifer beside drummer William Diamond.

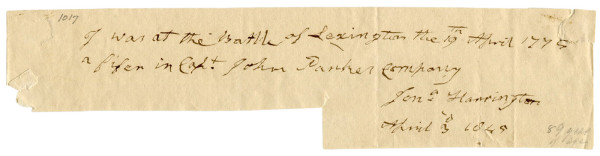

Fine content Autograph Note Signed, “Jon Harrington”, 1p. 48 x 196 mm. (1 7/8 x 7 3/4 in.), on an irregularly cut slip of paper, [Lexington], 30 April 1845, writing in full: “I was at the Battle of Lexington the 19th April 1775 a fife in Capt. John Parker’s Company”.

When Benson Lossing interviewed Harrington in 1848, the old soldier humbly explained that he only became one of the company’s musicians because he was the only person in Lexington who knew how to play a fife. Harrington recalled, “My mother… called out to me at three o’clock in the morning, ‘Jonathan, Jonathan! The reg’lars are coming and something must be done.’ I dressed quickly, slung my light gun over my shoulder, took my fife from a chair, and hurried to the parade near the meeting house, where about fifty men had gathered and others were arriving every minute. By four o’clock a hundred men were there. We did not wait long, wondering whether reg’lars were really coming, for a man darted up to Captain Parker and told him that they were close by. The captain immediately ordered … Joe[sic William] to beat the drum and I fifed with all my might. Alarm-guns were instantly fired to call distant minute-men to duty. Lights were now seen moving in all the houses. Daylight came at half-past four o’clock. Just then the reg’lars who had heard the drum beat, rushed toward us, and their leader shouted, ‘Disperse, you rebels!’ We stood still. He repeated the order with an oath, fired his pistol, and ordered his men to shoot. Only a few obeyed. Nobody was hurt, and we supposed their guns were loaded only with powder. We had been ordered not to fire first, and so we stood still. The angry leader of the reg’lars then gave another order for them to fire, when a volley killed or wounded several of our company. Seeing the reg’lars trying to surround us, Captain Parker ordered us to retreat. As we fled some shots were sent back. [William] and I climbed a fence near Parson Clarke’s house and took to the wood near by. Climbing over, [William] fell upon a heap of stones and crushed his drum-head. His hand was bleeding badly, and he found that a bullet had carried off a part of his little finger. Eight of our men had lost their lives.”1

Groomed for college, Harrington’s aspirations were dashed when the retreating regulars ransacked his home, taking the Latin books he needed to prepare, and burned them in the street. Harrington spent the remainder of his life as a farmer in Lexington. In his advanced age, Harrington’s association with the opening battle of the Revolutionary War gave him celebrity as veterans of the war died off. The curious, traveling from near and and far, made pilgrimages to his East Lexington home to hear his stories. 2 When he died in 1854, nearly 10,000 attended his funeral including the governor, both houses of the legislature and 1,000 soldiers.3

Tape repair to upper right corner slightly affecting the “5” in “1775”, light edge wear, overall very good condition.

(EXA 5222) SOLD.

_____________

1 Benson J. Lossing, Hours with the Living Men and Women of the Revolution, A Pilgrimage (1889), 2-8.

2 Mary B. Fuhrer, Research for the Re-Interpretation of the Buckman Tavern, Lexingon Massachusetts: Conceptions of Liberty (Unpublished report, 2012), 68.

3 “Funeral of Jonathan Harrington” Salem Register, (Mass.), 3 Apr. 1854, 2.